Why Food Date Labels Don’t Mean What You Think

on

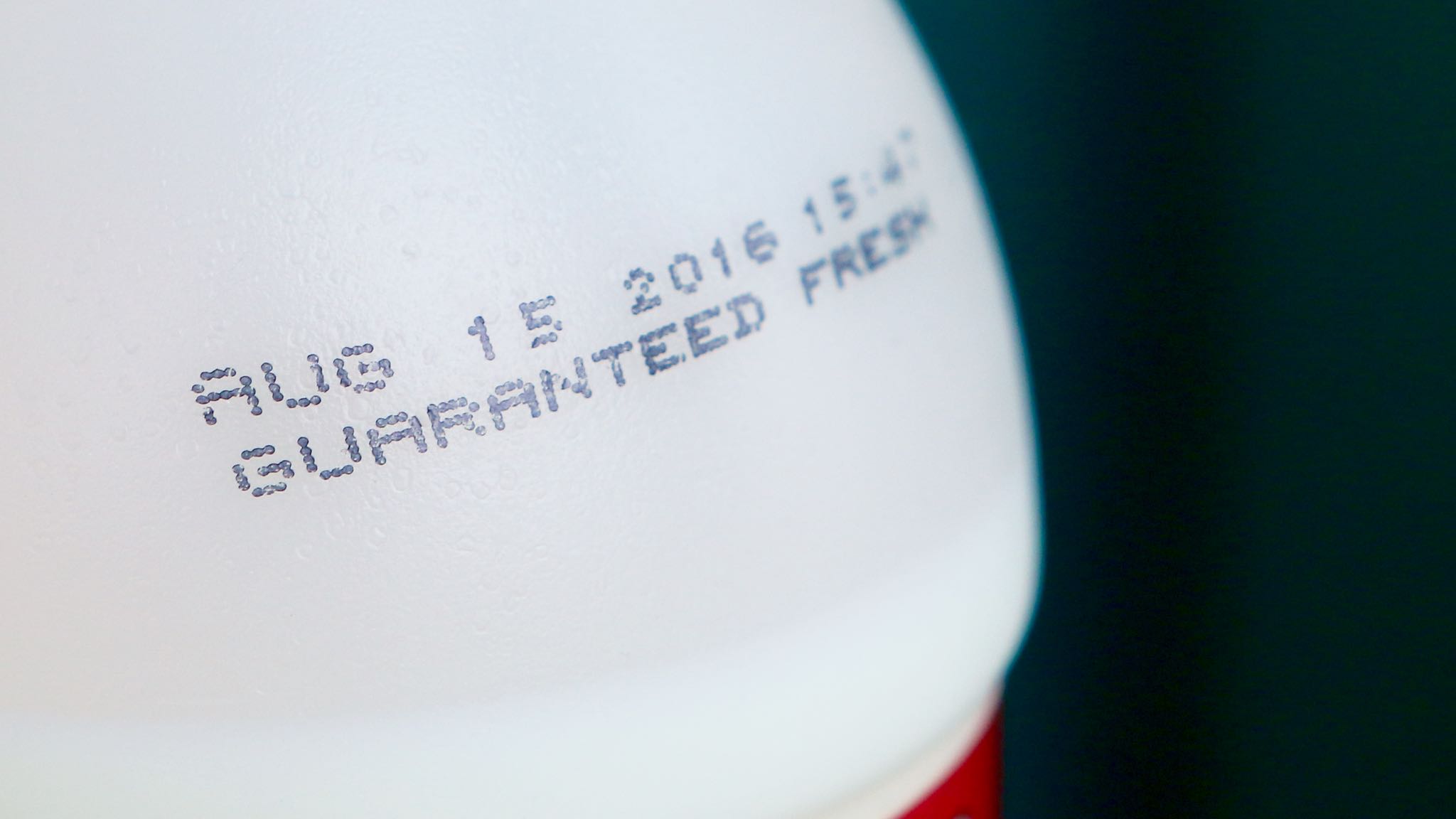

The dates printed on milk cartons are probably the six most misunderstood numbers in grocery stores.

First, let’s clear one thing up: It’s not an expiration date. Potentially harmful bacteria are destroyed in the pasteurization process. They can’t spontaneously regenerate, so old milk stored in the fridge doesn’t present an increased risk of foodborne illness.

So what is it? Often, the date is set for around three weeks after pasteurization, which is when the milk will begin to taste off. After reacting with oxygen and light, the fat in milk becomes rancid or stale. The distinct sour taste of aged milk is a byproduct of harmless lactic acid bacteria that feed on the sugar in milk. “It’s more of a sensory defect that we don’t like, but you’re not going to get sick on it,” says Randy Worobo, professor of food science at Cornell University.

Sixteen states prescribe by law the date on milk cartons, and some go a step further, regulating what happens to milk after that date. Montana requires milk to be thrown away 12 days after pasteurization, despite a lack of scientific evidence to support this practice.

Sometimes, the date is prefaced by the words “use by” or “best before.” Sometimes it’s a “sell by” date. Often it’s just a few cryptic numbers.

And the trouble with date labels extends beyond the dairy case and into the rest of the grocery store aisles.

“We do have a state of confusion in terms of date labeling,” says Donald Schaffner, professor of food science at Rutgers University. “Date labels primarily exist as a way for food manufacturers to communicate to their customers what to do or what to expect from the food product. There is not a lot of standardization.”

Confusion over date labels is a huge contributor to food waste. Americans trash an estimated 40% of viable food—upwards of 160 billion pounds per year—and misunderstandings about food date label comprises 20% of consumer food waste, based on a British study.

But there’s rarely reason to fret if your food is past date, says Emily Broad Leib, director of the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic. “There are a small handful of foods that shouldn’t be sitting in your refrigerator for such a long time—there is a safety risk. Whereas for all other foods it’s just about quality.”

Congress is currently considering a bill that would standardize food date labels and clearly distinguish manufacturer’s quality suggestions from scientifically based safety dates. It’s a simple fix that could save billions of dollars worth of food every year, and it would require almost no action on the part of consumers. Clarifying food date labels is the most cost effective way to combat food waste in the United States.

“Expires On”

In the world of food, the difference between “best by” and “expires on” is significant. “Everybody thinks it’s an expiration date when in fact it’s a best before date. And there’s a big difference,” Worobo says. Expiration dates are about food safety. Best before dates are about taste, texture and appearance, he says.

Only a small group of foods need expiration dates—primarily ready-to-eat foods like deli meats and prepared sandwiches, both foods which may contain bacteria like listeria and are not cooked immediately prior to consumption. Unlike other pathogenic bacteria, listeria is durable enough to grow at refrigerator temperatures. Recently cooked meats are safe from listeria—it dies at 160°F—but the expiration date on deli meats importantly reflects when listeria may have reached dangerous levels.

But most harmful bacteria, like Salmonella and E. coli, aren’t capable of growing on foods stored at cold temperatures or in dry conditions, like crackers in the pantry. “Microorganisms are no different than us—we need water, we need food, and we need the proper temperature to survive,” Worobo says. Depriving bacteria of their basic needs is the central philosophy of food storage.

Provided you do your part—keep foods refrigerated, wash fruits and vegetables, cook meat thoroughly and isolate raw meat from other foods—there’s a low risk of contracting a foodborne illness. And that risk usually doesn’t increase as food ages.

“If those lettuce leaves had no Salmonella at the start, then after it becomes a slimy disgusting mess, there will still be no Salmonella, because there’s no such thing as spontaneous generation—Louis Pasteur proved that,” Schaffner says. “Salmonella have to arrive from someplace—they don’t arrive from nothing. And the bacteria that turn that salad into a slimy disgusting mess, those bacteria don’t make us sick. I mean, they might turn our stomach, but they’re not infectious.”

To be clear, he’s not telling you to eat soupy lettuce—if a food item seems gross, throw it out. But if it looks and tastes okay a few days after the date, go ahead and eat it.

“Best If Used By”

For other foods—the vast majority—date labels are simply the manufacturer’s suggestion about when a product might taste freshest. “While shelf-life dating might be important for those products, it’s probably—and that’s a big asterisk there—not that important for food safety. It’s really about delivering to the customer a product that, at the end of its shelf-life isn’t a slimy disgusting mess,” Schaffner says.

But just because it isn’t likely to make you sick doesn’t mean the dates are arbitrary. Food ages in a staggering number of ways, making it nearly impossible to set uniform standards for shelf-life.

From the point of view of microbes, frozen pizza will never change. “From the day that it’s packaged in the manufacturer, 30 years out in your freezer, as long as it’s kept at that temperature, the microorganisms don’t grow,” Worobo says. That doesn’t mean it won’t change, though. Freezer burn is a common problem with frozen foods. It happens when water molecules, drawn to the drier environment outside the food, migrate out, only to then recrystallize on the outside, causing the burn.

Other foods like cookies and crackers, which are stable on store and pantry shelves for long periods of time, spoil for the same reason milk does. Over time, their fat reacts with the oxygen in the package, becoming rancid. The process—called oxidative rancidity—is what makes old crackers taste funky. “If you’ve never had a snack food past its shelf-life, try one,” Schaffner says. “It’s not going to make you sick, but it’ll taste gross.”

The texture of a cracker will probably change—it’ll lose its crispness as it draws water out of the air—but the moisture level inside an opened package “isn’t enough to support the growth of pathogens,” Worobo says. “It would never grow something that would make you sick. Unless you dunked it in contaminated water and they left it out at room temperature, then it would grow pathogens. But if you left it out on your counter—even after 30 years—it would not have pathogens growing on it.”

Food science labs typically determine a product’s shelf-life based on a combination of taste and microbial activity. “We do a lot of product evaluation studies in our lab,” says Willis Fedio, director of the food safety laboratory at New Mexico State University. They test—and taste—everything from potato salad to salsa and cookie icing. Every month or two he buys a batch of chicken wings and hosts a hot sauce tasting panel with the members of his lab. “I bribe them with wings and they fill out the forms.”

“We know what rancid tastes like,” Fedio says.

Legislating for Standardization

Because food labs and manufacturers use so many different criteria—bacteria levels, taste, texture—to determine a food’s shelf-life, it can be difficult to interpret what a date label means. The challenge of determining whether a date label indicates safety or quality is magnified by the many different conventions and labeling styles currently in use.

Representative Chellie Pingree of Maine and Senator Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut recently introduced a bill in Congress to standardize food date labels. Select foods that require safety dates will be labeled “expires on.” All other food labels will read “best if used by” to emphasize that it’s a quality date.

“There’s no way for the consumer generally to tell if the date that you see is the date it was manufactured, is the date that it ‘expires’, is the date that it’s best if you eat it by, or is a date after which you’ll get sick. Those labels become meaningless, and even if they have any basis in something, most of the time we don’t know what it is,” Pingree says.

Broad Leib and the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic recently studied how consumers react to the wide array of food labels currently in use: “best by,” “use before,” “sell by,” and more. “The words ‘use by’ are probably the most confusing,” Broad Leib says. People tended to interpret that label equally as a safety date and a quality suggestion.

“There’s going to need to be education no matter what term is used. We’ve been doing it this weird way for so long that didn’t have much meaning.” Broad Leib says. “If we suddenly want these to have meaning, we’re going to have to make that really clear to people.”

Of all the tens of thousands of foods in grocery stores, infant formula is the only food product whose date label is currently regulated by federal law. For everything else, state laws vary tremendously, covering different products or making conflicting recommendations about the same product.

Mitigating Food Waste

Pingree and Blumenthal’s legislation is a step toward standardizing and clarifying food date recommendations. “Sometimes we joke and say, ‘This should be the Domestic Harmony Bill,’ because we’re just trying to return happiness back into households or pantries,” Pingree says.

More than that, though, Pingree wants to address the billions of dollars Americans spend on wasted food. It’s estimated that 90% of Americans throw food away after the date for safety reasons, unsure whether it will make them sick of not.

“The largest cause of household consumer food waste is not knowing if you should throw something away or not, and I’ve seen studies that show the most cost effective thing we could do to reduce food waste is to bring some sort of uniformity, education, sensibility, into our date labeling system,” Pingree says.

A Food Giant Lumbers Forward

Not everyone is waiting on an act of Congress, though. Inspired by a report from the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic highlighting the problems with food date labels, Walmart decided to investigate their own labeling practices.

The company surveyed how companies that made their Walmart-brand foods decided to date label the items. “We discovered that our food suppliers were date labeling them 47 different ways,” says Frank Yiannas, vice president of food safety for Walmart.

They recently moved from 47 labels to just one. All of Walmart’s private brand food is labeled with “best if used by”. Walmart’s research—coinciding with Harvard’s independent further research—determined the phrasing to be clearest to consumers.

Even with standardized date labels, the reason for a “best if used by” label will change depending on the food. “I don’t think there’s a one-size fits all approach,” Schaffner says. “The problem is that all foods are different. The way that I’m going to label my bacon is going to be different than the way that I’m going to label a cookie or cracker, which is going to be different than how I label my milk.” The food’s date hints at the best time to consume it, but the date alone won’t tell you if most food is spoiled—only your tastes can.

“For the vast majority of spoilage, it’s mostly an ick factor,” Worobo says.