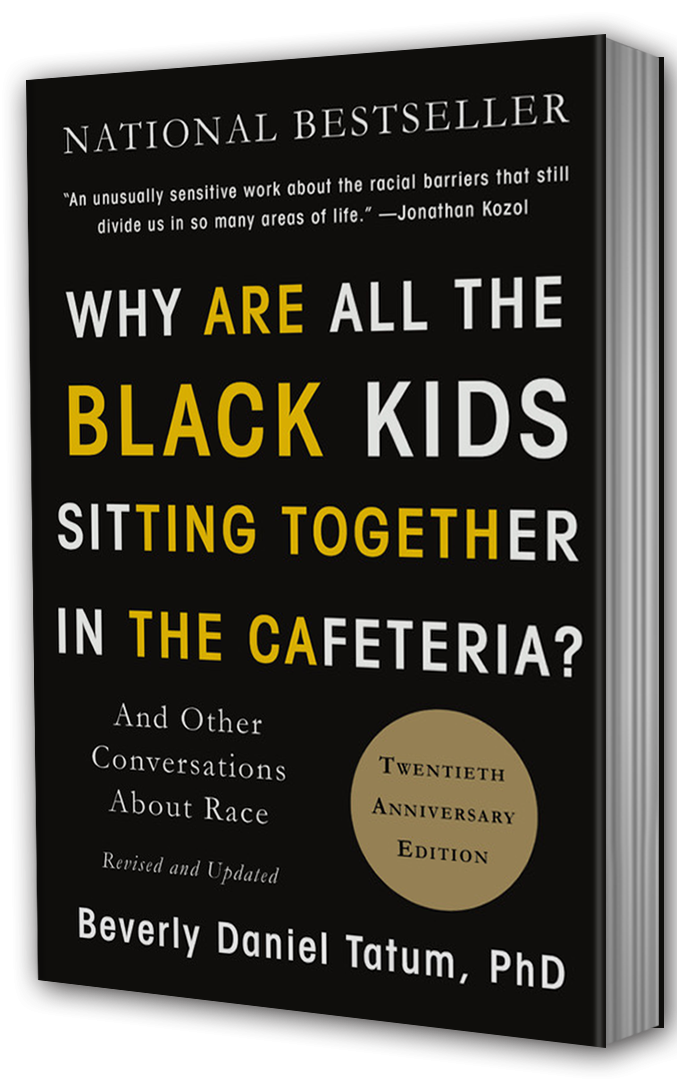

“Some people say there is too much talk about race and racism in the United States. I say that there is not enough,” writes psychologist and author Beverly Daniel Tatum.

Twenty years ago, Tatum published a book tackling how different racial groups self-segregate, and what that tells us about the psychology of racism – and just how uncomfortable we are confronting it.

Tatum has now released an updated and expanded version of the best-seller: “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations About Race.”

Tatum, president emerita of Spelman College in Atlanta, joins Chicago Tonight for a conversation.

Read an excerpt of the book below.

![]()

Donald Trump’s election emboldened White nationalists who celebrated his victory in public gatherings. Less than two weeks after the election, a White nationalist conference took place in Washington, DC, just a few blocks from the White House, embracing Donald Trump’s election as validation of their ideas. Not only had their preferred candidate been victorious, but he had quickly selected as his senior adviser and chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon, the man who had previously run Breitbart News, the most prominent media platform of the so-called alt-right. With Bannon as part of Trump’s inner circle, the opportunity for White nationalists to influence presidential politics seemed a dream come true.195

For others, the days after the November 8 election were something out of a nightmare. Immediately after the election, hostile graffiti appeared. For example, in Durham, North Carolina, walls at a busy intersection read, “Black lives don’t matter and neither does your votes.” In Wellsville, New York, a baseball dugout was spray-painted with a swastika and the words “MAKE AMERICA WHITE AGAIN.” National and local newspapers were filled with stories about the dramatic rise in bias-based attacks after the election.196

For others, the days after the November 8 election were something out of a nightmare. Immediately after the election, hostile graffiti appeared. For example, in Durham, North Carolina, walls at a busy intersection read, “Black lives don’t matter and neither does your votes.” In Wellsville, New York, a baseball dugout was spray-painted with a swastika and the words “MAKE AMERICA WHITE AGAIN.” National and local newspapers were filled with stories about the dramatic rise in bias-based attacks after the election.196

The Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate-motivated incidents, released a report called Ten Days After documenting almost nine hundred reports of harassment and intimidation, not including online harassment, that were reported within the first ten days of the election. In these documented accounts from across the nation—every state is represented—many of the harassers invoked Trump’s name during assaults, making it clear that the outbreak of hate stemmed in large part from his electoral success. According to the SPLC report, people have been targets of harassment at school, at work, at home, on the street, on public transportation, in their cars, in grocery stores and other places of business, and in their houses of worship. The most common occurrences involved hateful graffiti and verbal harassment, although a small number of the events included violent physical interactions. Only 23 of the 867 incidents reported were directed at the Trump campaign or his supporters.197

The detailed accounts are upsetting to read. They include: multiple reports of Black children being told to ride in the back of school buses; the words “Trump Nation” and “Whites Only” being painted on a church with a large immigrant population; a seventy-five-year-old gay man being pulled from his car and beaten by an assailant who said the “president says we can kill all you faggots now.” Though SPLC has been documenting similar hateful incidents for many years, the people targeted since the election said this experience was new for them

“I have experienced discrimination in my life, but never in such a public and unashamed manner,” an Asian-American woman reported after a man told her to “go home” as she left an Oakland train station. Likewise, a black resident whose apartment was vandalized with the phrase “911 nigger” reported that he had “never witnessed anything like this.” A Los Angeles woman, who encountered a man who told her he was “Gonna beat [her] pussy,” stated that she was in this neighborhood “all the time and never experienced this type of language before.” Not far away in Sunnyvale, California, a transgender person reported being targeted with homophobic slurs at a bar where “I’ve been a regular customer for 3 years—never had any issues.”198

The SPLC reports that schools—K–12 settings and colleges—have been the most common venues for hate incidents. For example, a Washington State teacher reported: “‘Build a wall’” was chanted in our cafeteria Wed [after the election] at lunch. ‘If you aren’t born here, pack your bags’ was shouted in my own classroom. ‘Get out spic’ was said in our halls.” Another example was provided by a mother from Colorado: “My 12-year-old daughter is African American. A boy approached her and said, ‘Now that Trump is president, I’m going to shoot you and all the blacks I can find.’”199

The hurtful words of children can be frightening. Even more so are the physical acts of violence committed by adults. The hijab, the traditional head scarf worn by Muslim women in public, makes them easily identifiable for those who would target them. Less than a week after the election, a Muslim student at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, was forced to remove her hijab by a man who threatened to set her on fire if she didn’t.200 Two Muslim women were attacked in New York City, just two days apart. In one case, a man pushed a transit worker down a staircase at Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan, yelling, “You’re a terrorist and you shouldn’t be working for the city.” In another, a Brooklyn man threatened an off-duty police officer and her teenaged son, both American-born, with his pit bull, telling them to “go back to your country.” The first man escaped, but the second was arrested and charged with a felony hate crime.201

In response to these and other incidents, New York governor Andrew Cuomo and mayor of New York Bill de Blasio both spoke forcefully about them. Said Governor Cuomo, “This is the great State of New York—we welcome people of all cultures, customs and creeds with open arms. We do not allow intolerance or fear to divide us because we know diversity is our strength and we are at our best when we stand united.” Mayor de Blasio held a news conference with the Muslim police officer, Aml Elsokary, at his side, saying: “This is Officer Elsokary’s country. She is an American. She is a New Yorker. She’s already at home. We cannot allow this kind of hatred and bias to spread.”202

Civil rights advocates called on Donald Trump to demonstrate his own leadership and speak out against the harassment and denounce extremist groups, but his response seemed slow in coming, particularly given his propensity to send messages quickly on Twitter, as demonstrated throughout his campaign. In his 60 Minutes interview that aired on November 13, 2016, President-Elect Trump claimed that he was “surprised to hear” that some of his supporters had been using racial slurs and making threats against African Americans, Latinxs, and members of the LGBT community. He took the opportunity to look into the camera and send a message to his audience, saying, “Stop it!”203 On November 21, Hope Hicks, a Trump spokesperson, said, “Mr. Trump has always denounced these groups and individuals associated with a message of hate. . . . Mr. Trump will be a president for all Americans. However, he totally disavows the support of this group, which he does not want or need.”204 Are those statements sufficient to undo the damage of his campaign rhetoric? Probably not. The authors of the SPLC report called for more demonstrable leadership from Donald Trump. They write, “Rather than simply saying ‘Stop it!’ and disavowing the radical right, he must speak out forcefully and repeatedly against all forms of bigotry and reach out to the communities his words have injured. And rather than merely saying that he ‘wants to bring the country together,’ his actions must consistently demonstrate he is doing everything in his power to do so.”205

His early personnel selections left many wondering if that kind of consistent anti-bias action was likely to come from his administration. Following the controversial choice of Stephen Bannon, he nominated Senator Jeff Sessions of Alabama for the role of attorney general. In that role, Sessions would be responsible for enforcing civil rights laws, but his record in Alabama as a US attorney is one of wrongly prosecuting Black voting-rights activists and opposing the Voting Rights Act.206 More recently, as a member of the Senate, Sessions was the first to endorse Donald Trump’s candidacy and is described as “one of the most strident anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, anti-L.G.B.T. voices in the Senate.”207

Donald Trump campaigned on the promise to deport millions of undocumented immigrants right at the beginning of his administration, a promise that has left a whole generation of young people and their families worried about their future. Some children, born in the United States, are citizens but worry what will happen to their undocumented parents, and to them, if family members are deported. Others arrived in the US as young children and, though they grew up in the US, don’t have the protection of citizenship. Through executive action, President Obama implemented the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy in 2012. The policy allows young people who entered the country without authorization before the age of sixteen and have lived in the US continually since 2007 the opportunity to work and go to school without fear of deportation. Young people protected by DACA must seek renewal of that legal protection every two years. Because the policy was created by executive order, rather than through the legislative process, it can easily be reversed by a new president with a different executive order. During his campaign, Trump indicated his intent to do so. Those who registered for DACA status are now part of a government database and consequently will be easy to find if the new president moves forward with his threats to engage in mass deportations.

Fear and anxiety on the part of some White people may have been a key driver of the election results. The election outcome has created considerable fear and anxiety among communities of color and their White allies. How will the new president of the United States address the concerns of all of the people? In December 2016, as I write these words, the answer to that question remains to be seen.

What we do know is that leadership matters. How the leader describes who is in and who is out matters on a college campus, and it matters in our nation. Living in a time of rapid social change, one might ask, well, how am I supposed to manage my anxiety and my fear—by lashing out? Earlier, in reference to the election of President Obama in 2008, I spoke of “birthing pains” because something new was emerging, and perhaps it still is. But let us be clear: the moment of birth can be a dangerous time. And I think we are living in a dangerous time and should take that danger seriously.

When I listened to the polarizing rhetoric of radio and TV commentators during the long 2016 election campaign season, full of “us-them” language, I was reminded of a book I read a few years ago, Left to Tell by Immaculée Ilibagiza, a survivor of the Rwandan genocide. She wrote about the hostile rhetoric that was on the radio airwaves before and during the genocide, demonizing the ethnic minority to which she belonged. That rhetoric was made especially powerful because it came from the country’s leaders.209

I do not mean to suggest that what we are seeing in the US today is on par with what was happening in Rwanda. But I do want to make clear that what we say matters, and leadership matters. The expectations and values of leaders can change the tone of the community and the nature of our conversation. Fundamentally, we know that human beings are not that different from other social animals. Not unlike wolves, we follow the leader. Yes, we have an innate tendency to think in “us” and “them” categories, but we look to the leader to help us know who the “us” is and who the “them” is. The leader can define who is in and who is out. The leader can draw the circle narrowly or widely. When the leader draws the circle in an exclusionary way, with the rhetoric of hostility, the sense of threat among the followers is heightened. When the rhetoric is expansive and inclusionary, the threat is reduced. It sounds simple, but we know it is not.

The leader has to ask the question, how is the circle being drawn? Who is inside it? Who is outside it? What can I do to make the circle bigger? As Martin Luther King Jr. once said, we are caught in a “network of mutuality,” and that means our collective fate is intertwined. We will thrive or fail together.

And here’s what we must also consider: If a person is twenty years old in 2017, born in 1997, all the critical issues I have written about in these pages thus far are the coming-of-age hallmarks of their generation. Having been born in 1954 in segregated Florida and raised in Massachusetts as part of the Great Migration out of the Jim Crow South, I—and others of my generation—have a long personal history with social progress. I saw Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on television in real time. I heard his and others’ speeches and watched the March on Washington on the nightly news. I saw people who had been denied the right to vote exercise that right for the first time on television. I have seen the colleges and universities at which I was educated and at which I have worked grow more diverse over time. That sense of racial progress is part of my generation’s lived experience. Yet for those born in 1997, all of that is something in their history books. Their perspective is shaped by a very different set of events.

If you were born in 1997, you were eleven when the economy collapsed, perhaps bringing new economic anxiety into your family life. You were still eleven when Barack Obama was elected. You heard that we were now in a postracial society and President Obama’s election was the proof. Yet your neighborhoods and schools were likely still quite segregated. And in 2012, when you were fifteen, a young Black teenager named Trayvon Martin, walking home in his father’s mostly White neighborhood with his bag of iced tea and Skittles, was murdered and his killer went free. When you were seventeen, Michael Brown was shot in Ferguson, Missouri, and his body was left uncovered in the streets for hours, like a piece of roadkill, and in the same year, unarmed Eric Garner was strangled to death by police, repeatedly gasping “I can’t breathe” on a viral cell phone video, to name just two examples of why it seemed Black lives did not matter, even in the age of Obama. When you were nineteen, Donald J. Trump was elected president and White supremacists were celebrating in the streets. How would a twenty-year old answer the question posed to me, “Is it better?” The answer to that question would probably depend a great deal on the social identities of that twenty-year-old.

We have lived through a political campaign season in which we heard the president-elect and his campaign surrogates saying things like, “We’re taking America back.” Back to what? Back from whom? What is their definition of “better”? What is yours? We have a lot of work to do if we are to truly move forward together as a nation.

I hope that, in the chapters that follow, readers will find tools that help them better understand themselves and other people and how we are all shaped by the inescapable racial milieu that still surrounds us and that, in some ways, has grown more opaque and seemingly more impenetrable. Twenty years after I first wrote these chapters, how we see ourselves and each other is still being shaped by racial categories and the stereotypes attached to them. The patterns of behavior I described then still ring true because our social context still reinforces racial hierarchies, and still limits our opportunities for genuinely mutual, equitable, and affirming relationships in neighborhoods, in classrooms, or in the workplace. For that reason, this twentieth-anniversary edition will be quite familiar to those who have read earlier editions. The opening chapters of the book (Chapters 1–3) have updated citations but remain essentially the same in content. Chapters 4–9 have been completely rewritten, with new reference material and expanded discussion. Chapter 10 remains much the same as in the original edition and is followed by a new epilogue, “Signs of Hope, Sites of Progress.” The epilogue is offered as a remedy for despair, my effort to highlight people and places that are making a positive difference and, in doing so, point us in a direction that might change our current trajectory, so twenty years from now, we can say without hesitation, “Yes, it is better.” Shall we begin?

Excerpt from Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations About Race by Beverly Daniel Tatum. Copyright © 2017. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.