Mayor Rahm Emanuel, center, and Chicago police Superintendent Eddie Johnson welcome police recruits in Chicago on May 21, 2018. After Officer Jason Van Dyke killed Laquan McDonald, Emanuel replaced police chief Garry McCarthy with Johnson. (Antonio Perez / Chicago Tribune)

It was a case of police abuse that riveted the nation. Videotaped violence, under the cloak of darkness, at the hands of uniformed cops. Cries for reform and soul searching in the halls of power. Ultimately, the political pressure prompted the big-city mayor to abandon re-election plans.

Was this Baltimore in 2015? No. The death of Freddie Gray while in police custody prompted Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake to forgo a re-election campaign, but there was no videotape. Cleveland in 2017? Not hardly. Mayor Frank Jackson was re-elected, even after the police killing of Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old carrying a pellet gun in a public park.

The case in question occurred in Los Angeles, circa 1992. Riots erupted after a jury with no African-American members acquitted four white cops despite videotaped evidence they brutally beat Rodney King, an African-American motorist. Longtime Mayor Tom Bradley decided to step down.

More than a quarter century after the King riots, violence in the streets remains a defining issue in mayoral elections across the country. Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel is not immune, and he seems to know it. When thousands of people marched down the Dan Ryan Expressway last weekend, the protest signaled that street violence and police reform will be defining issues of Chicago’s 2019 mayoral campaign.

In fact, two of Emanuel’s leading opponents owe their political viability to the crime issue. Former police chief Garry McCarthy was Chicago’s top cop the night Officer Jason Van Dyke gunned down 17-year-old Laquan McDonald, firing 16 shots as the knife-wielding McDonald walked away from him. McCarthy did not resist Emanuel’s decision to stall the release of the dash-cam video that documented the shooting until after the 2015 mayoral election, but he now is criticizing the decision and Emanuel’s policing strategy.

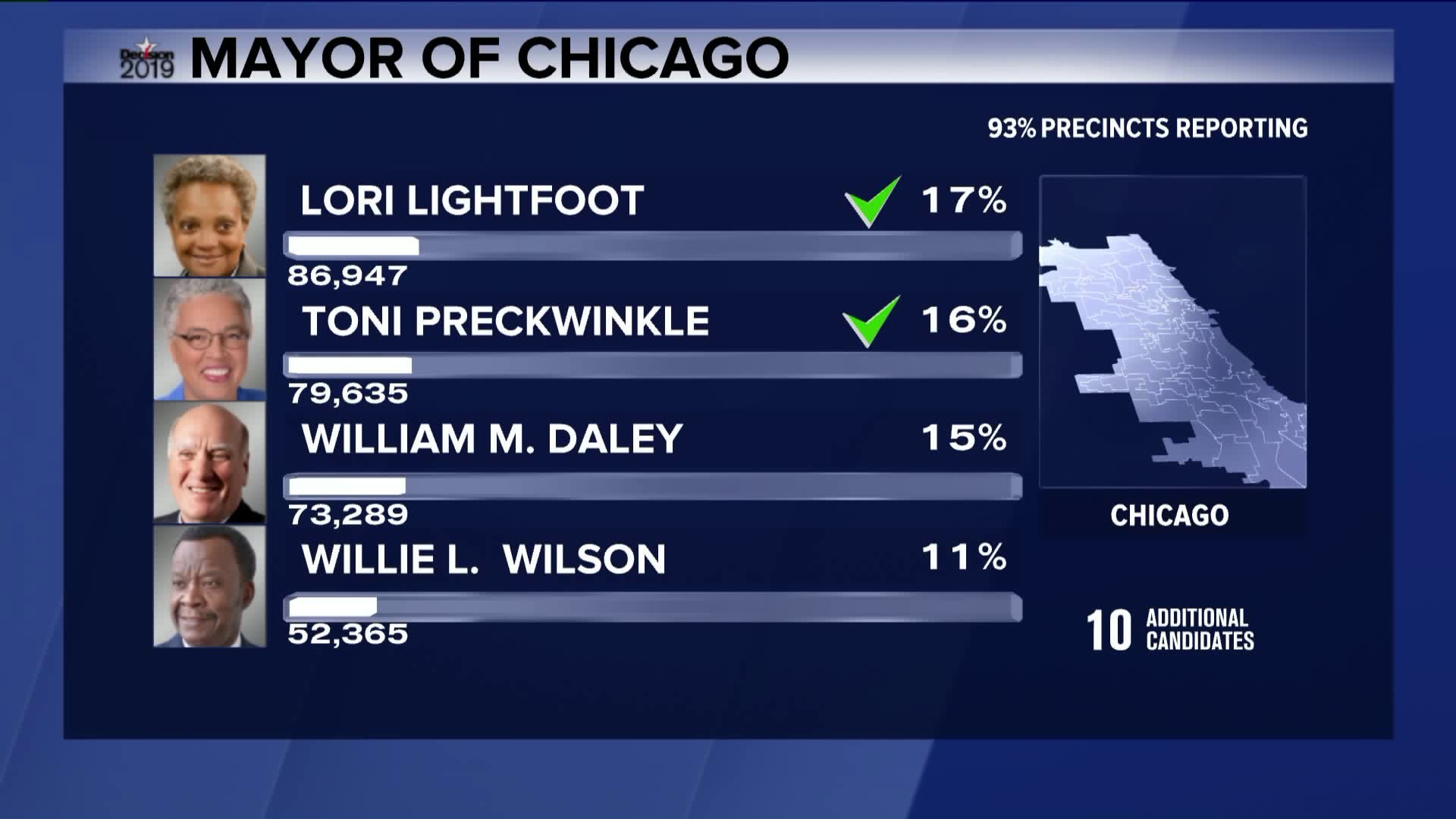

Meanwhile, mayoral challenger Lori Lightfoot was appointed three times to police oversight positions. Emanuel named her to the Police Accountability Task Force, formed after the McDonald shooting, which declared racism among Chicago police was rendering the force ineffective in the neighborhoods.

Raphael Sonenshein, executive director of the Pat Brown Institute for Public Affairs at California State University in Los Angeles, has studied the impact of the King case on Los Angeles politics and sees lessons for Mayor Emanuel and his challengers.

After the King riots, city politics were cleaved between conservatives pushing for law and order and progressives who believed neglect and racism had caused the police and civil breakdowns. The city began to recover only after reforms that led to meaningful change. A commission led by former Secretary of State Warren Christopher delivered a brutally candid assessment of police department failings. A polarizing police chief was removed. A ballot initiative brought about structural change. Ultimately, a federal consent decree locked in reforms.

“The quality of reform in Los Angeles was pretty remarkable,” Sonenshein said. “It was like watching a country convert from autocracy to democracy.”

EDITORIAL: Go ahead, sign Pat Quinn’s term limits petition »

Emanuel has gotten only part way there. After firing McCarthy days after releasing the McDonald videotape, he selected a chief from the CPD ranks, Eddie Johnson, who has shown strong community skills. The mayor’s deployment of technology to fight crime is beginning to show results, though not nearly fast enough. Still, Emanuel has made mistakes. After initially saying he would agree to a federal consent decree on police reform, he briefly flirted with an out-of-court settlement with Jeff Sessions’ Justice Department. A backlash — and a lawsuit by Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan — prompted him to reverse field and begin negotiating a consent decree with Madigan that eventually will seek court approval. It’s been a twisted path, to say the least, and created a political vulnerability that Lightfoot already has attacked.

Emanuel’s response to last weekend’s march showed he may finally be gaining his political footing on the violence issue. He publicly supported the marchers even before the event, then tweet-slapped Gov. Bruce Rauner after Rauner tweeted a call for “a quick and decisive end to this kind of chaos.” There was no chaos, only an orderly expression of free speech, calling for reform.

Protecting Chicago’s neighborhoods from violence, of all kinds, will take more than nimble tweeting. A consent decree would help, but will be relevant in the mayoral campaign only if Emanuel and Madigan get it done before voters go to the mayoral primary election in February.

Lightfoot, McCarthy and other mayoral candidates can’t just stand on the sidelines and snipe. They will need to show they have better ideas — and withstand the inevitable critiques from Emanuel and his backers. The fight for support from African-American preachers and politicians will be intense.

Days after the Dan Ryan march, Emanuel was in China negotiating to prevent President Donald Trump’s tariffs from scuttling the city’s $1.3 billion purchase of Chinese-made CTA trains. He has led a downtown building boom and adroitly recruited McDonald’s and other companies to move their headquarters downtown. Unemployment in Chicago is at its lowest point in Emanuel’s two terms in office.

In the mayoral race that’s taking shape, none of that may add up to much. Street violence and police reform can become all-consuming issues that win — and lose — mayoral elections.

In Los Angeles, Tom Bradley dropped out rather than stay in the fight. That’s one path Emanuel certainly will not follow.

David Greising is president and chief executive officer of the Better Government Association.