The Unknown History of Latino Lynchings

(Warning: this article contains images that some may find disturbing. Viewer discretion is advised.)

(Warning: this article contains images that some may find disturbing. Viewer discretion is advised.)

The following is a summary & analysis of Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review article, “Law of the Noose: A History of Latino Lynching” by Richard Delgado.

SUMMARY

Delgado attempts to shed light on a largely unknown history of Latinos, particularly Mexican-Americans in the Southwest U.S., who were lynched between the years of 1846 and 1925. This is roughly the same time that many Blacks were lynched in the U.S., as well. While many know of the ominous and horrific fate that Blacks and African-Americans saw in the U.S., few know of the lynchings that Latinos were met with. Delgado challenges scholars and institutions by trying to unveil the truth on this shameful past, while exploring the history of these lynchings and explaining that “English-only” movements are a present-day form of lynchings.

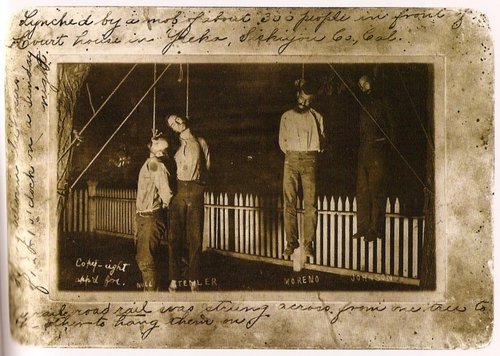

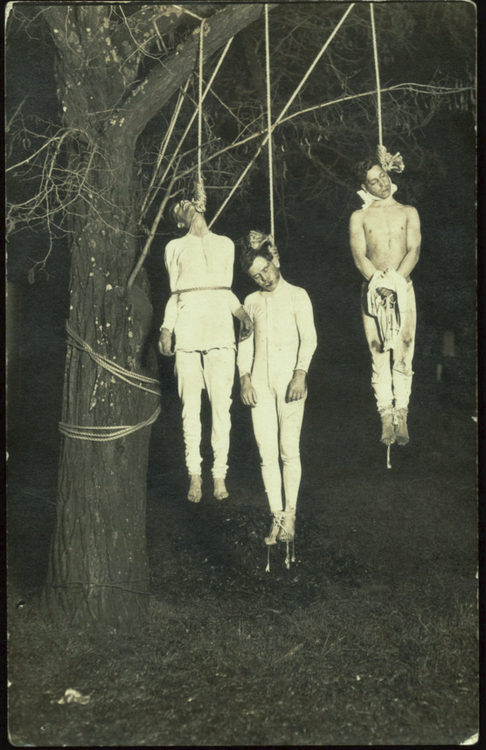

Although research on Latino lynchings is relatively new, circa 2006-2009, lynchings have a deep rooted history. Such acts can be described as mob violence where person(s) are murdered/hanged for an alleged offense usually without a trial. Through reviewing of anthropological research, storytelling, and other internal & external interactions, there is believed to have been roughly 600 lynchings of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans beginning with the aftermath of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (this document essentially ended the Mexican-American war, where Mexico surrendered half of its land to the U.S.). This grim fate of Blacks & Mexicans in the U.S. was intertwined; both groups were lynched by Anglos for reasons such as “acting uppity,” taking jobs away from Anglos, making advances toward Anglo women, cheating at cards, practicing “Witchcraft,” and refusing to leave land that Whites coveted. Additionally, Mexicans were lynched for acting “too Mexican;” for example, if Mexicans were speaking Spanish too loudly or showcasing aspects of their culture too defiantly, they were lynched. Mexican women may also been lynched if they resisted the sexual advances of Anglo men. Many of these lynchings occurred with active participation of law enforcement. In fact the article reiterates that the Texas Rangers had a special animus towards persons of Mexican descent. Considering that Mexicans had little to no political power or social standing in a “new nation,” they had no recourse from such corrupt organizations. Popular opinion was to eradicate the Southwest of Mexicans.

Many of these lynchings were treated as a public spectacle; Anglos celebrated each of these killings as if the acts were in accordance with community wishes, re-solidifying society and reinforcing civic virtue. Ringleaders of such lynchings often mutilated bodies of Mexicans, by shooting the bodies after individuals were already dead, cutting off body parts, then leaving the remains on display perhaps in hung trees or in burning flames.

These lynchings took place in the Southwest U.S., in present-day Texas, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Nevada, amongst other states. The killings were carried out by vigilantes or other masked-men, as a form of “street justice.” These killings became so bad that the Mexican government lodged official complaints to the U.S. counsel in Mexico. Given that this region of the U.S. was at one time Mexican land, and it was shared with Indian/Indios, Mexicans, and Anglos, protests against the lynchings emerged. As legend has it, Joaquin Murrieta took matters into his own hands by murdering the Anglos responsible for the death of mythical figures Juan Cortina and Gregorio Cortes. Such acts were short-lived and perpetuated the conflict between Mexicans and Anglos.

These lynchings took place in the Southwest U.S., in present-day Texas, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Nevada, amongst other states. The killings were carried out by vigilantes or other masked-men, as a form of “street justice.” These killings became so bad that the Mexican government lodged official complaints to the U.S. counsel in Mexico. Given that this region of the U.S. was at one time Mexican land, and it was shared with Indian/Indios, Mexicans, and Anglos, protests against the lynchings emerged. As legend has it, Joaquin Murrieta took matters into his own hands by murdering the Anglos responsible for the death of mythical figures Juan Cortina and Gregorio Cortes. Such acts were short-lived and perpetuated the conflict between Mexicans and Anglos.

Delgado goes on to cite that only some U.S. historians have written about these Latino lynchings and have pointed out that they occurred due to racial prejudice, protection of turf, and Yankee nationalism left over from the Mexican-American War. However, it has been concluded that such lynchings are a relatively unknown history due to a global pattern of shaping discourse as to avoid embarrassment of the dominant group. Those in power often have the ability to edit official records.

Further exploration reveals that these lynchings were not only edited & minimized outright, but were also ignored or misrepresented due to primary accounts in community newspapers being written in Spanish. Since very few mainstream historians read Spanish or consulted with these records, they were left to flounder. Also, many Latinos knew of these lynchings; their accounts were maintained, shared, and solidified as Mexican lore through ritualistically songs (corridos, actos, and cantares). Many oral cultures have equivalences of such interpretations. Today, Latino scholars are not surprised by history’s ignoring of such events; postcolonial theory describes how colonial societies almost always circulate accounts of their invasions that flatter and depicts them as the bearers of justice, science, and humanism. Conversely, the natives were depicted as primitive, bestial, and unintelligent. Subsequently, colonialists must civilize the natives, use the land & its resources in a better fashion, and enact a higher form of justice. The “official history” is written by the conquerors, thus showing them in the best possible light.

Delgado questions whether such remnants of Latino lynchings may still be present in society today. This can best be exemplified through movements to make English the official language of the U.S., forcing immigrants to assimilate to the dominant Anglo culture. Such actions can be illustrated in movements to end bilingual school opportunities and enforce English-only speaking at jobs, businesses, etc. Postcolonial scholars argue that such movements facilitate children to reject their own culture, acquire English, and forget their native language. These actions have far dire [documentable] consequence, like social distress, depression, and crime. As such, Delgado ventures to say that these actions are an implicit form of lynching.

Delgado ends the piece by saying that hidden histories of aggression, unprovoked war, lynchings, and segregation are corroborated/proliferated today by the mass media and entertainment industry. These groups, along with other scholars, have the opportunity to redress this history and reject further practices against Latinos. Otherwise, marginalized groups find themselves in a position where they are alienated from their family/identity/culture, co-opted, and unable to resist further oppression.

ANALYSIS

Such history is imperative to the framework of Americana and for acknowledgement purposes, not only because it is a matter of fact, but because this history is relevant to the ancestors of the land. History has always been exploited to benefit those who are in power, so to maintain their structures. However, today, I would argue that current powerbrokers would gain more respect & credibility by being honest with themselves and the actual history. Continuing to deny or ignore the history does an injustice to all. Current Chicanos, Mexican-Americans, and Americans alike would most benefit from this restoration for a few reasons.

First, a corrected version of history helps the people better understand themselves. Americans, Mexicans, the fusion of the two, in addition to people of the world, would recognize a better sense of their true identity & culture. The exploration of such history can perhaps allow for analysis of current rates of depression, crime/incarceration, and socioeconomic status(es). If we, the people, want to understand ourselves, we need to know the truth.

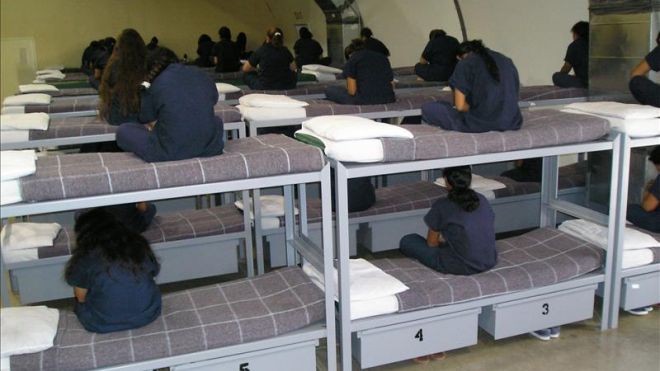

Secondly, if we want to understand why things are the way they are today, we can look to history. This shameful past can assist us in the interpretation of Mexican/American relations. Additionally, I believe that this understanding will help both groups reach a common ground with current relations. Since the year 2000 alone, the FBI has reported over 2,500 hate crimes against Latinos based on race and ethnicity. The U.S. is marred with a nasty & stalled immigration battle that is masked for hatred against Mexicans. In 2014, there is a continued, on-going crisis at the Southwest border affecting many children and families. With the history of these lynchings, it is now time for the “greatest country in the world” to make the wrong things right.

Again, we know that history can repeat itself, but only if we let it. Thus, the entire world needs to be educated on the true history of these lynchings. The more we are educated on such atrocities, the less likely we will allow them to happen again. Attacking the access of this knowledge is the third reason to explore this history. Ignoring the disastrous past does not make the history go away. With the knowledge of the truth, the Latino people can empower themselves to conquer stereotypes and achieve further greatness. Most Chicano/Latino studies programs in schools allow students to learn about their past while achieving higher marks. But in states like Arizona, educational officials have banned Chicano/Latino Studies in schools, and as a result have not allowed students to know the true history of the land they currently inhabit. This is not only a further atrocity, but it reaffirms Delgado’s point that current lynchings, lynchings of the mind, are happening today. This is blatant lying and it is unacceptable; when we lie to our government, we go to prison. When our government lies to us, it’s no big deal.

Furthermore, for those who are tired of people of color in the U.S. raising points of contention about racial issues in this country, you now see the justification. This is why we won’t be quiet about racism, racial prejudice, discrimination, etc. This is why we’ll march in the streets for the Trayvonn Martin’s, reject the school to prison pipeline, and continue to spread awareness until administrative action is taken on a grand scale. Today’s generation is a bi-product and reflection of this history; not only are these “lynchings” continuing to happen, but the masterplan has worked. In order to achieve our full capabilities, we need to reject a fragmented history and seek a personal revolution, which starts with ourselves. And we can achieve this revolution through education & knowledge.

Be empowered.

Maximo Anguiano is a scholar, actor, and creative. Follow him on Twitter orFacebook.

REFERENCES

The Law of the Noose: A History of Latino Lynching. R. Delgado (2009). Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 44, 297-312.

Lynchings in the West, Erased from History and Photos. K. Gonzalez-Day (2012). New York Times.