By Linda Lutton, WBEZ; Andrew Fan, City Bureau; Alden Loury, WBEZ

Published June 2020

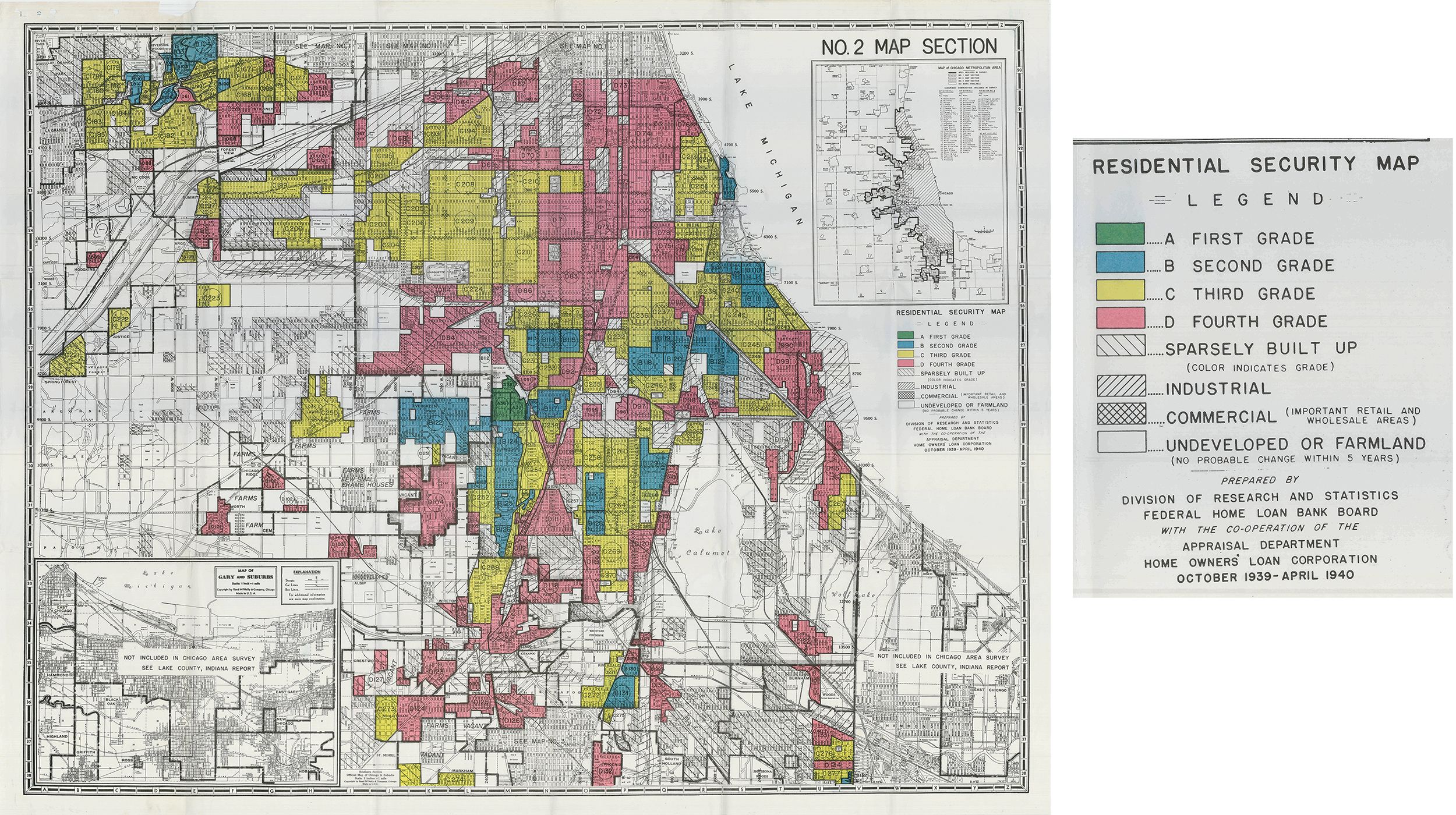

Eighty years ago, the federal government drew red lines around Chicago’s black neighborhoods and warned banks not to make home loans there.

Today, discrimination in housing is outlawed, and federal regulations are supposed to ensure banks lend in all neighborhoods.

But a new analysis by WBEZ and the nonprofit newsroom City Bureau shows gaping disparities in the amount of money lent in Chicago’s white neighborhoods compared to black and Latino areas — a pattern that locks residents out of home ownership, deprives communities of desperately needed capital investment and threatens to exacerbate racial inequities between neighborhoods.

WBEZ and City Bureau examined records for every home purchase loan made in Chicago that was reported to the federal government from 2012 through 2018 — 168,859 loans totaling $57.4 billion for residential properties ranging from condominiums and single-family homes to large apartment complexes. The loans were made by traditional banks but also “non-bank” mortgage companies, which now give out more than half of all home loans in Chicago.

We found:

-

68.1% of dollars loaned for housing purchases went to majority-white neighborhoods, while just 8.1% went to majority-black neighborhoods and 8.7% went to majority-Latino neighborhoods.

In other words, for every $1 banks loaned in Chicago’s white neighborhoods, they invested just 12 cents in the city’s black neighborhoods and 13 cents in Latino areas. That’s despite the fact that there are similar numbers of majority-white, black and Latino neighborhoods in the city.

-

The gaps in home purchase lending were even wider for some of the city’s largest lenders.

JPMorgan Chase, for instance, lent 41 times more money in white neighborhoods than black neighborhoods.

-

Lenders invested more money in majority-white Lincoln Park than they did in all of Chicago’s majority-black neighborhoods combined.

The same was true for three additional majority-white community areas. Lake View, the Near North Side and West Town each individually attracted more investment than all of Chicago’s majority-black neighborhoods combined.

-

While some of the disparity in dollars lent is explained by higher home prices in white areas, there was also a disparity in the sheer number of loans.

Financial institutions made four times more loans in Chicago’s white neighborhoods than they did in black or Latino areas.

“The private market works in white communities. The private market does not work effectively in black communities,” concludes Nedra Sims Fears, executive director of the Greater Chatham Initiative, which promotes homeownership in several historically middle-class neighborhoods on Chicago’s South Side. “It wasn’t set up to work, and it has not worked.”

Sims Fears has seen up close what it looks like when banks and other financial institutions don’t lend. It means homes don’t sell, properties sit vacant. It means families who want to invest in a neighborhood can’t. It creates a cycle in which it’s harder for everyone to buy and sell.

The Greater Chatham Initiative runs trolley tours of the area for potential homebuyers. Dozens of participants pack trolleys and buses. Despite the interest in home buying, the amount of money banks lend in Chatham and other black neighborhoods lags behind the capital banks pour into majority-white neighborhoods. (Linda Lutton/WBEZ)

Studies of mortgage lending frequently focus on denial rates for borrowers, comparing how often African American homebuyers are turned down for loans compared to white borrowers, for instance. The WBEZ/City Bureau analysis is different. We look at how the total amount of money flowing into Chicago communities through home loans is tied to the race of the neighborhood.

Money injected into neighborhoods through home loans is a critical way capital moves into communities, one that has broad impacts on how neighborhoods look and feel, and how life is lived by residents.

Money injected into neighborhoods through home loans is a critical way capital moves into communities, one that has broad impacts on how neighborhoods look and feel, and how life is lived by residents.

“[Lending for home purchases] determines whether you have a pharmacy to shop at or a dry cleaner to go to,” said Brett Theodos, a senior fellow with the Urban Institute who has studied flows of capital to neighborhoods in Chicago and other cities. “It determines what rehabilitation work is going to happen to the multifamily stock that’s in your neighborhood. It determines what other single-family stock is going to be coming to your neighborhood.”

Theodos said home purchase lending is the single largest type of investment in Chicago neighborhoods, accounting for some 60% of all capital flows and dwarfing money lent by the city, state and federal government.

Plotting home purchase lending for Chicago neighborhoods on a map shows investment piled high over white neighborhoods, while lending in many black and Latino neighborhoods is hardly visible.

To be sure, higher home prices in white areas explain some of the disparity in lending. But those higher home prices are themselves a reflection of past and present lending practices. For instance, banks for decades failed to lend in black neighborhoods. That has led to many homes in those areas needing expensive repairs. But because the homes need repairs, lenders are hesitant to provide home purchase loans. A lack of lending depresses property values. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle.

Some disparities in lending are understandable, said Kristin Faust, who served until last year as president of Neighborhood Housing Services of Chicago (NHS), a nonprofit that makes home loans almost exclusively in black and Latino areas. She’s now head of the Illinois Housing Development Authority.

Faust said properties near the lake, public transit or other amenities naturally command higher prices and thus attract more lending dollars. But she said that doesn’t explain what’s happening in Chicago, where lopsided lending far favors North Side white areas. Public transit lines run all over the city, said Faust, and there is lakefront along the entire South Side.

So sure, location matters, said Faust. “But what that map shows, and what in Chicago we have got to address, and what is not OK is that it’s also totally linked to race.”

In fact, current lending in Chicago is so closely tied to the race of the neighborhood, it’s reminiscent of redlining maps from 80 years ago.

Maps created by the federal government from 1935 to 1940 graded areas by their “mortgage security.” (Mapping Inequality)

The current mortgage lending numbers suggest that Chicago is on a path to exacerbate inequities between its majority-white neighborhoods and its black and Latino communities, even as Mayor Lori Lightfoot has promised to tackle Chicago’s stubborn reputation as a “tale of two cities” and channel more capital to black and Latino neighborhoods.

Chicago’s biggest banks show huge racial disparities in lending

While lenders in Chicago collectively put 8.4 times more money in white communities than black communities, individual lenders had even more unequal records.

JPMorgan Chase had the widest white-to-black disparity among the city’s top home purchase lenders. The bank loaned 41 times more in Chicago’s white neighborhoods than it did in the city’s black neighborhoods. That means for every dollar the bank loaned in white neighborhoods, it invested just 2.4 cents in the city’s black communities.

From 2012 to 2018, Chase loaned nearly nine times more in a single majority-white community — Lake View on the North Side — than it did in all of the city’s majority-black neighborhoods combined.

And Chase is not alone. Bank of America lent 29 times more money in Chicago’s white communities than it did in black communities and 21 times more in white communities than in Latino neighborhoods. Wells Fargo lent 10 times more in white areas than black and 17 times more in white areas than Latino. And the city’s largest home purchase lender, Guaranteed Rate, lent 15 times more in Chicago’s white communities than its black communities, and over 11 times more in white areas than Latino.

WBEZ and City Bureau found instances where banks take in millions of dollars in deposits but give out few home loans. For instance, Chase has two branches in Chatham that hold a total of $80 million, but from 2012 through 2018, the bank made just 23 home purchase loans there. That’s roughly three loans per year in the historically middle-class black neighborhood.

In 2017, Chase made a high-profile pledge to invest $40 million over three years in Chicago to promote economic opportunity on the city’s South and West sides. “We understand that those are areas that, through the years, really have had some struggles with participating in the broader economy,” an executive with the bank explains in a promotional video.

But if Chase had loaned in black communities what it loaned in majority-white neighborhoods from 2012 to 2018, that would have meant an additional $829 million each year for Chicago’s black neighborhoods. Even if Chase had simply made loans in black neighborhoods at the same disparate rate as the overall market, that would have meant an additional $80 million in Chase investments every year for Chicago’s black neighborhoods.

Lake View, Chicago

Received about $6 billion in home purchase mortgage loans from 2012-2018 — more than all of Chicago’s majority-black neighborhoods combined.

Chicago’s Latino communities do not see much more lending than the city’s black neighborhoods.

But some home ownership advocates working in Latino neighborhoods say they feel they’re up against a bigger threat than weak lending — rising home prices and property taxes. In fact, homeownership counselors at the nonprofit LUCHA, in Humboldt Park, said if they were to see lending amounts increase in Latino neighborhoods, that might signal higher home prices and gentrification, which they say is making it harder for longtime neighborhood residents to purchase property.

At The Resurrection Project in the historically Latino Pilsen neighborhood, homeownership counselor Lizette Carretero said it can be hard to recognize lending disparities from the trenches.

“It goes unseen,” said Carretero, who said advocates have lots of ideas about how banks might improve their lending record in Latino communities and “transfer those dollars over to the neighborhoods that need them.” She suggests lending to DACA recipients, offering significant down payment assistance and making it easier to get rehab loans so families could purchase “as-is” properties that need fixing up.

Lenders respond

Lenders contacted by WBEZ declined to give on-the-record interviews for this story, but a number sent written statements, and some took issue with WBEZ’s analysis.

“Guaranteed Rate made more loans in minority neighborhoods during the seven-year period covered by this story than any other lender,” a spokesperson for the online lender wrote. “Chicago is our home, and we are serving our entire community.”

A Chase home lending spokesperson did not offer a reason why the bank’s black-white lending disparity is so much wider than even the industry as a whole. She said Chase has doubled its homebuyer grants on the South and West sides and is expanding access to low down payment loans. She also pointed to the bank’s support for affordable housing. “Every Chicagoan should have equal access to the opportunity of homeownership, and we all have work to do for this to happen,” the spokeswoman wrote.

Chase Bank has branches in both Englewood (left) and Lincoln Park (right). From 2012-2018, the bank loaned $1.7 million across Englewood and West Englewood, and $980 million in Lincoln Park. (Manuel Martinez/WBEZ)

Bank of America said the analysis failed to provide a full picture of its home mortgage lending since it excluded refinance loans, which accounted for 57% of its lending in Chicago in the years analyzed. A spokeswoman said refinances helped keep people in their homes. Bank of America’s lending disparities were less when it came to refinancing, but the bank still had more disparate lending than the industry as a whole. WBEZ excluded refinance loans from our analysis to avoid double counting capital flows.

Like Chase, Bank of America also pointed to work with local nonprofits to promote homebuyer education and counseling, and highlighted grants that pay for closing costs and help with down payments.

Wells Fargo pointed out it recently received the highest possible rating from the federal government for its performance under the Community Reinvestment Act. Lenders are graded on different benchmarks under that law than what WBEZ used in its analysis.

Overall, banks pointed out that higher home prices in white areas mean there are more dollars lent there. Lenders criticized WBEZ for failing to compare demand for loans and borrower qualifications across white, black and Latino neighborhoods.

The fallout in neighborhoods

Community residents say the disparate lending has tangible and pernicious impacts on their day-to-day lives.

“First of all, you impact the number of homeowners who live here,” said Asiaha Butler, executive director of the Resident Association of Greater Englewood (RAGE). And for Butler, homeowners are key to turning around the community’s struggle with poverty, crime, abandoned buildings and vacant lots. “Getting people to really look at Englewood as a place to invest, and to purchase properties that are here and available — we have a lot of homes that could be renovated or owner occupied.”

Asiaha Butler is the executive director of the Resident Association of Greater Englewood, which started a campaign to help residents buy homes. (Linda Lutton/WBEZ)

RAGE started a “Buy the Block” campaign to encourage residents to become property owners — and community interest has been strong; she’s packed meeting rooms with potential buyers. But Butler said big banks seem disinterested.

“We have banks here. Chase is here. Bank of America is here. U.S. Bank is here,” Butler said. Yet over the last seven years, across Englewood and West Englewood — communities spanning six square miles in the heart of Chicago’s South Side — those three major banks collectively made just 33 home purchase loans.

Bank of America, Chase Bank and U.S. Bank branches in Englewood. (Manuel Martinez/WBEZ)

“It kills me because you have a room full of 150 people willing to do what they have to do to purchase property in Englewood,” Butler said. “They can’t get a loan to do that, because of their ZIP code, because of their race. … How can I promote that, if our lenders are not on the same side?”

Good income, good credit, good assets — no loan

Our findings show that stark lending disparities affect even middle-class black communities.

Sims Fears, the director of the Greater Chatham Initiative, organizes trolley tours that wind through her historic South Side community of stately brick two-flats and bungalows to highlight homes for sale. The trolleys are typically packed with people eager to buy in Chatham.

But in late 2018, Sims Fears got her own rude lesson in lending when she put in an offer to buy the former home of “Mr. Cub,” Ernie Banks. The 3,500-square-foot bungalow with wraparound front windows sits on a quiet corner at 82nd and Rhodes. The living room features built-in shelves backed with red felt where the baseball great displayed his trophies.

The property needed work. The windows wouldn’t open, lights didn’t turn on. Sims Fears talked the seller down to $160,000.

The former home of Ernie Banks, which Greater Chatham Initiative Director Nedra Sims Fears bought last year. (Linda Lutton/WBEZ)

But when she went to get a bank loan, she ran into problems, even though Sims Fears and her husband have good incomes, credit scores and assets. They planned on doing $200,000 worth of work on the house.

That’s when appraisers calculated that even with all-new electricity, plumbing, windows, air conditioning, a modern kitchen and a mother-in-law suite, the remodeled house would be worth only $300,000 — shockingly low.

Sims Fears stands in a room she is remodeling in her house. (Linda Lutton/WBEZ)

Sims Fears believes there’s one reason for that, the same reason red lines were drawn around neighborhoods back in the late 1930s — the house is in a majority-black neighborhood. The low appraisal meant Sims Fears couldn’t borrow the money she needed to do the repairs and upgrades, even though she could easily afford the loan.

Her lender told her she had one option: go back to the seller and talk them down further.

“So it’s like they were saying, ‘OK, so this house — this 3,500-square-foot, three-bedroom house — is only worth $100,000,’” she said.

It was a moral question for Sims Fears. Here she is, neighborhood booster, telling folks to buy into this historic black neighborhood, invest, build wealth for your family. Now, she felt like the system was telling her to steal the wealth another family had built up.

“And I said, ‘Well, I’m not going to do that. I’ll make up the difference.’”

So Sims Fears took $60,000 from her family’s savings and put it into the house to get the loan.

“Just to close,” said Sims Fears.

Sims Fears stands in the living room of her home, surrounded by tools being used to refurbish the house. The built-in shelves behind her, backed with red felt, are where Ernie Banks once displayed his baseball trophies. (Linda Lutton/WBEZ)

Studies have concluded that homes in black neighborhoods are consistently under-valued — which affects the amount of money buyers can get from lenders, and often whether they can purchase at all in a particular neighborhood. If Sims Fears hadn’t put her own money into the deal, she may not have been able to get the home. It’s unlikely it would have passed inspection in its original “as-is” state — another reason banks give for not lending.

Zeke Morris said what Sims Fears experienced is not unusual. “The house that Nedra lives in — put that house at 4000 north, that house is worth $1.2 million, easily — the very same house,” said Morris, who oversees two dozen realtors at EXIT Strategy Realty on the South Side. He estimates that in 30% to 40% of cases where the buyer and seller come to an agreement on price on Chicago’s South Side, appraisers determine the home is worth less, and the bank won’t lend at the agreed-upon price.

“And a lot of times those deals — they die as a result of that,” Morris said.

Houses in Austin, a majority-black neighborhood, (left) and houses in Lake View, a majority-white neighborhood (right). Lake View and Austin have similar populations, but Lake View received about 12 times as much lending. (Manuel Martinez/WBEZ)

Sims Fears is a particularly savvy observer in all this. She served as an assistant commissioner for housing under Mayor Harold Washington in the 1980s. And she worked for Fannie Mae in the 2000s, developing loan products to fit the needs of lower-income communities across 10 states in the Midwest. She said that’s what financial institutions need to do for Chicago neighborhoods: come up with loans that work better for Chicago’s black and Latino neighborhoods. She’d like to see loans based on borrower qualifications, not home values — loans that require less money down, smaller loans, loans that allow for significant rehab.

She said banks need to “look at their disparities and how they can make it up.”

But Sims Fears also sees a role here for the city.

She said Chicago needs to see its housing stock as part of the city’s infrastructure — like sewer pipes or roads. Something that needs to be invested in.

She said Chicago needs to see its housing stock as part of the city’s infrastructure — like sewer pipes or roads. Something that needs to be invested in.

That could take lots of forms, Sims Fears said. What about equity insurance in black neighborhoods so homeowners can be sure their homes won’t go below a certain value? Or a pool of rehab money for people whose homes — because of depressed property values — need more repairs than the structures are supposedly worth.

Why no lending?

Discrimination in lending can take place without anyone intending to discriminate, said Lauren Nolan, who has researched mortgage lending in Chicago for the Woodstock Institute, a group founded 40 years ago in part to watchdog these very lending numbers.

“We don’t have the same level, necessarily, of the overt discrimination that we saw during the redlining era. What we’re seeing now is more systemic racism,” she said. “It is, in some respects, a new form of redlining — de facto.”

“What we’re seeing now is more systemic racism. … It is, in some respects, a new form of redlining — de facto.”

Nolan said the Community Reinvestment Act, the federal law meant to force banks to lend in all communities, needs to be strengthened. Currently, 98% of banks get passing grades under the act, according to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, which works to end discrimination in lending. Banks are not judged by the metrics WBEZ and City Bureau examined in this analysis.

Experts say past discrimination fuels today’s inequities.

“These patterns that we’re seeing today are a product of that history of disinvestment,” said Geoff Smith, executive director of the Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University.

The fact that banks denied loans in African American neighborhoods previously means properties there need significant rehab, said Smith. That depresses home values today and makes it difficult to get a loan on properties across entire neighborhoods, even for qualified buyers.

Austin, Chicago

Received about $508 million in mortgage loans from 2012-2018

And since overt discrimination limited African American homeownership decades ago, black families have less wealth today to pass down — wealth that could help with down payments to create the next generation of homeowners.

Home prices across many of Chicago’s African American neighborhoods have still not recovered following the housing crash, and many homeowners there remain under water. Those conditions help explain why banks steer clear.

“There’s these layers and layers of challenges,” said Smith.

Sims Fears said profit motive plays a role; she’s been told that banks don’t want to make mortgages for less than $200,000. “They really want the larger mortgages,” which cost about the same to underwrite, but offer lenders more profit, she said. Large banks tend to donate to small community lenders and leave the smaller market to them. The banks “just look like they’re closed for business,” said Sims Fears.

Of course, out-and-out discrimination is still another possible reason for lending disparities. The U.S. Department of Justice has found banks discriminate against neighborhoods with significant Latino and African American populations, and journalists have reported on other examples.

What’s at stake for communities and families

Whatever the causes, the impact of unequal lending is as pernicious today as it has been in past decades. In addition to shaping neighborhoods right now, today’s inequitable lending is the landscape on which Chicago’s future will be built.

Nonprofit groups are lending in neighborhoods where banks are not. But their volume is minimal, and they have not been able to make up for a lack of lending in the private market.

Faust, the former president of Neighborhood Housing Services, said that organization began making loans in neighborhoods four decades ago to fill gaps where banks weren’t lending.

Forty years later, those gaps haven’t closed. NHS has become a top lender in recent years in some neighborhoods, including Woodlawn, Roseland, North Lawndale and Greater Grand Crossing — sometimes with just a handful of loans.

“It is exciting in one way,” Faust said about becoming a lead lender. “But it actually is not OK in another very big way. We’re a small nonprofit loan fund. You would think the banks, they might be in a better place to take some risk.”

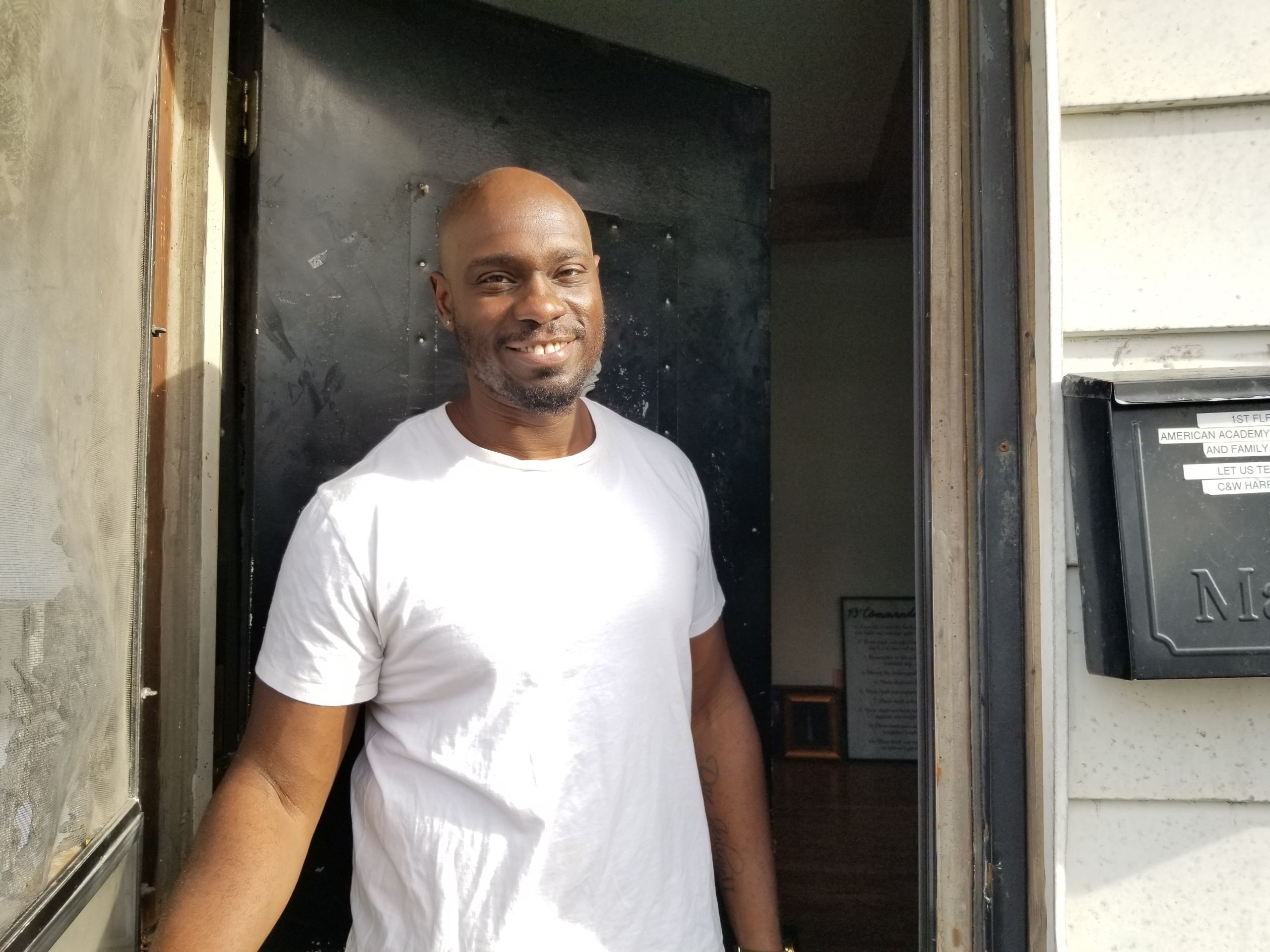

Dax Jemison bought his grandmother’s home in Greater Grand Crossing on the South Side thanks to a loan through NHS. Standing in his remodeled kitchen, he said the home has been transformational. Yes, Jemison knows he’s building wealth for his young family. But homeownership has touched him in ways he didn’t expect. It’s like a “getaway,” he said. “If you take a vacation to a place that you’ve never been, and it’s just like, ‘Wow! This is available? This is on this Earth?’ That’s how our home feels for us.”

Dax Jemison opens the door to his home in Greater Grand Crossing, a place he says feels like “a vacation” to him and his family. (Linda Lutton/WBEZ)

“I could sit back here and just look out this doggone window all day and just appreciate where I am,” said Jemison, looking out on his tiny backyard. “Now my next goal, my next step is to really bring up the community.”

He’s got ideas to turn vacant lots into parks. He wants more businesses on the commercial strips. And he thinks the house next door — currently boarded up — could really use a homeowner.

Andrew Fan led City Bureau’s home lending reporting team in 2019. Follow him on Twitter at @afan.

Alden Loury is the senior editor of WBEZ’s Race, Class and Communities desk. Follow him on Twitter at @AldenLoury.

Linda Lutton covers Chicago neighborhoods for WBEZ. Follow her on Twitter at @lindalutton.

How we did this story

City Bureau and WBEZ analyzed data that financial institutions are required by the federal Home Mortgage Disclosure Act to compile and publicly report. For this story, we looked at every home purchase loan that originated in the city of Chicago between 2012 and 2018. We included single-family home loans as well as loans for condominiums, two- and three-flats and also larger multifamily apartment buildings. We tallied up lending by census tract. We calculated the majority race of each census tract using 2013-17 data from the American Community Survey. You can download the data table that drives our analysis here.

Where Banks Don’t Lend

Home Loans in Chicago: One Dollar To White Neighborhoods, 12 Cents To Black

In Chicago, lenders have invested more in a single white neighborhood than all the black neighborhoods combined. Call it modern-day redlining.

How The Green Line, A Pink House And 12 Cents Changed How I See My City

I always wondered why the city’s mostly white neighborhoods looked so different than its black neighborhoods. Then I looked at 168,859 home loans.

One Small Project At A Time’: What The City Lost When Its Black-Owned Banks Closed

The former CEO of Chicago’s last black-owned bank describes how they built African-American wealth loan by loan.