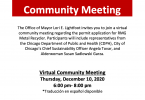

Info Shared by Alderwoman Garza:

Editor’s note: This story was originally published on June 21, 2005, as part of a weeklong series to commemorate the 25th anniversary of “The Blues Brothers.” The Sun-Times is republishing the stories to mark the 40th anniversary in 2020.

In “The Blues Brothers,” John Belushi’s character was so inspired by “preacher” James Brown he glowed — radiating in a beam of light — and then he flip-flopped down the center aisle of the Triple Rock Church.

In real life, on any given Sunday, arm-waving children, dressed in bright purples, blues, yellows and greens, dance enthusiastically at the Pilgrim Baptist Church of South Chicago, where the movie was filmed. Colorful bonnets — from turquoise to pink to white — dot the pews.

The music is loud and powerful, and the Rev. Hillard Hudson, holding his hands in the air and wearing a coat laced with crosses, screams, “There is nothing wrong with celebrating for Jesus!” Parishioners shout back, “Hallelujah!” and “Praise the Lord!”

It’s a scene only slightly less energetic than Brown’s over-the-top rendition of “The Old Landmark” in “The Blues Brothers.” The scene pays homage to Chicago as the birthplace of gospel.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20043079/3_27_Lachat_blues_5.jpg)

The 88-year-old Pilgrim Baptist church is still alive and well at 3235 E. 91st, although it has gone through changes since the Blues Brothers went to “get wise” and “get to church,” as Cab Calloway, in the role of their orphanage mentor Curtis, urged them to do.

Although the interior of the church was shot in Hollywood, the re-creation was so exact that the pastor at the time wondered if film crews had sneaked inside.

As it was, crews filmed outside — a glorious shot that showed off the large, leaning cross atop a high steeple — and in a vestibule as the Blues Brothers head inside. That steeple — which led locals to coin the name “Church with the Crooked Cross” — was why director John Landis decided to film there, he said.

The movie producers paid to install stained-glass windows in front of the church to match the intricate ones in the rest of the building. Since then, however, most of the original stained glass sits covered in dust in a back storage area because the church can’t afford to have them repaired.

The church now looks very different. It recently completed a $150,000 renovation that provided the first fresh coat of paint in years, new fixtures, a new roof and new flooring.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20043101/2_Screen_Shot_2020_06_18_at_10.24.08_PM.png)

But with a 200-member congregation that is half the size it was at the time of filming, the church — like the neighborhood around it — is a shadow of its former self. The shell of an education center sits behind the church, but the church couldn’t afford to complete it. And the 8-foot leaning cross was taken down for repairs and never re-installed.

Steel mills and related business once employed some 20,000 people of mixed heritage in the South Chicago neighborhood, which sits in the shadow of the former South Works mill. Now the area is largely Latino and African American, said Pilgrim Baptist congregant Brad McKinnon, 52.

The biggest blow was the shutdown of the South Works plant in 1992. “There was a severe employment shortage,” Hudson said. Said congregant Rosa Thomas, 62: “It went from good to worse.” Drugs moved in and the neighborhood deteriorated.

But in recent years the area has seen a turnaround, with new housing going up and a revived Commercial Avenue nearby. “We’re bouncing back,” said Neil Bofanko, executive director of the South Chicago Chamber of Commerce.

A Chicago developer is in the process of buying nearly half of the former South Works site. Solo Cup had planned to build a factory on another part of the site, providing 1,000 jobs, but those plans fell through. Hudson says some congregants who moved away have started attending the church again.

Even as the neighborhood has changed, Blues Brothers tourists from all over the world have sought out the church and sat in on services. While some church members complain about not getting paid enough in relation to the $115 million box office gross of the movie, others are still flattered.

“It was gratifying to the neighborhood to pick our church,” McKinnon said. “It made us a landmark.”