The question that haunts Martin Luther King’s last day in Memphis

Click Link To View Video:

https://www.cnn.com/2018/04/03/us/mlk-memphis-what-if/index.html

Civil rights icons remember MLK 50 years later 02:25

(CNN)It’s April 4, 1968, and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. steps outside his room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, and leans over the balcony.

King has been in an anxious mood all day, and his room reflects his hurried state of mind. His bed remains unmade, and his suitcase — containing his hair brush, clothes, a can of Magic Shave and a copy of his book, “Strength to Love” — remains unpacked.

As King stands on the balcony, he asks a saxophonist in the courtyard below to play his favorite song, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” at a rally he’s leading later that night.

Across the street, a man raises his rifle in the narrow bathroom of a derelict rooming house and points it at King. It is 6:01 p.m.

Just as the man squeezes the trigger, King suddenly returns to his room to don his overcoat against the evening chill. The bullet misses King’s head by inches and slams into a wall.

close dialog

American history is full of grim what-if questions. What if President Lincoln’s bodyguard had not decided to get a drink and leave Lincoln unguarded that night at Ford’s Theatre? What if Robert Kennedy had decided not to take a shortcut through the kitchen at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, where an assassin was waiting for him on the night he was killed?

As the nation remembers King’s assassination in Memphis 50 years ago, there’s another largely unspoken question: What if King had survived? Would he have changed the trajectory of events that shaped a post-1968 America? And how would events have changed him as the country evolved?

I asked those questions of some of the people who knew King best. They include a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer whose work revealed some of King’s most private inner struggles, scholars who have studied and taught King’s life for decades, and a close friend who was with King at the Lorraine Motel and remembers his peculiar mood during his last moments.

They cited four possible scenarios, had King lived. These may seem trivial to consider in light of King’s murder. But part of the reason so many people still deeply mourn King a half-century later is not just because of what the world lost — it’s the tantalizing possibility of what more it could have gained.

He would have outflanked the ‘Southern strategy’

Some commentators talk about the white backlash, or “whitelash,” that greeted President Obama’s election. But the United States was already undergoing a whitelash when King was assassinated.

Many white Americans in 1968 thought the civil rights movement had gone too far. Segregationist Gov. George Wallace of Alabama tapped into that racial resentment while running for president. He drew huge crowds in the North and won nearly 10 million votes in the 1968 general election as a third party candidate.

What Wallace started, Richard Nixon refined.

Nixon won the 1968 presidential election as a Republican in part by deploying what some historians call “the Southern strategy.”

Clay Risen, author of “A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination,” described that strategy in a recent New York Times editorial.

“Nixon played to the middle by eschewing the overt racism of George Wallace,” Risen wrote.

“But he deployed a range of more subtle instruments — anti-busing, anti-open housing — to appeal to the tens of millions of white suburbanites who imagined themselves to be racially innocent, yet quietly held many of the same prejudices about the ‘inner city’ and ‘black radicals’ that their parents had held about King and other civil rights activists.”

That backlash rolled on in other ways. There was a violent reaction to busing in places like Boston in the 1970s. The Supreme Court made school integration more difficult with cases like Milliken v. Bradley, and weakened affirmative action programs in college with Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, a case prompted by a white law student who said he was a victim of reverse discrimination.

The impact of that white backlash lingers. The Republican Party is predominately white. Public schools in America are even more segregated than they were in the 1960s. And the private lives of millions of Americans remain segregated as well. Most whites don’t have any nonwhite friends.

Could King have stopped any of this?

Yes, says the Rev. William Barber, the force behind “Moral Mondays,” an interracial social justice movement formed in North Carolina in 2013. He has revived King’s Poor People’s Campaign this year with a series of marches and job walkouts. The new campaign is planning to launch six weeks of nonviolent civil disobedience on May 13, Mother’s Day.

“King was killed at the very time that we needed to expose this strategy,” Barber says. “When he was killed, it almost gave the Southern strategy and Christian nationalism a path to hijack the public discourse.”

King would have outflanked the Southern strategy, Barber says, by showing working class white Americans in clear and dramatic ways that they had common cause with all working people.

When King was killed, he was forming an interracial army of poor whites, Hispanics, Native Americans and blacks to camp out on the Mall in Washington and demand that Congress stop funding the Vietnam War and fight poverty instead. He was going to demand a $12 billion Economic Bill of Rights to guarantee jobs for the able-bodied, income to those unable to work and an end to housing discrimination.

Images of King speaking out on behalf of poor white people would have sent a powerful signal to alienated whites who were starting to flock to the Republican Party, Barber says.

“You wouldn’t have had the ability to split poor whites and blacks, because the Poor People’s Campaign would have brought them together,” he says. “You wouldn’t have gotten a Nixon and a Reagan.”

You wouldn’t have gotten five more years of Vietnam, either, another historian says.

King was assassinated exactly one year to the day after he delivered a speech opposing the Vietnam War. It was one of the most unpopular decisions he ever made. President Lyndon B. Johnson abandoned him, and many black and white allies denounced him.

King’s anti-war speech, though, won him new fans in the growing anti-war movement — which was bolstered even more when Robert Kennedy began to oppose the Vietnam War.

King could have saved thousands of lives in Vietnam, had Kennedy, who was running for president in 1968, also survived, says Benedict Giamo, associate professor of American Studies at the University of Notre Dame.

“I think it would have been a quicker end to the Vietnam War with a coalition of MLK and RKF,” says Giamo, who teaches a course called “Witnessing the Sixties.” “As we know, from ’68 to ’73, you had close to 25,000 more deaths in Vietnam.”

King’s anti-war speech was prophetic. The United States gradually turned against the Vietnam War, and today it is seen as a major blunder. And King’s Vietnam speech is seen as one of his finest moments.

He would have been pushed aside by blacks and whites

Historians get nostalgic about King’s Poor People’s Campaign, but for many who were involved in his last crusade, there is little nostalgia. Many were exhausted by 1968, and some of his close aides didn’t support it.

“Even the staff people weren’t that enthusiastic,” says Bernard Lafayette, who was a close friend of King and the national coordinator for the campaign, which was led by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

“The enthusiasm that should have been there was not there,” he says. “It seemed so hopeless. How do you help poor people?”

The nation is still trying to figure that out. The Poor People’s Campaign ended in June, when police closed down a camp that had been set up by demonstrators near the Lincoln Memorial, and arrested those who resisted.

Almost everything that happened to the Poor People’s Campaign would have happened even if King had been there — and it would have “hurt King’s stature tremendously,” says Jerald Podair, a history professor at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin, and author of “Bayard Rustin: American Dreamer.”

“He was going to lose the white working class to Nixon and Reagan no matter what,” Podair says. “He was assassinated in April, and only six months later Nixon was elected.”

King’s economic message would have been just as controversial in the 1970s as his racial message was in the 1960s, Podair says.

King had evolved to become a “democratic socialist” much like Bernie Sanders is today, Podair says. He would have pushed for a government-run national health program, a national jobs program and a guaranteed income for Americans.

Maybe that resonates with those who voted for Sanders when he ran for president in 2016. But that kind of economic message would not have gained traction in the ’70s and ’80s, Podair says.

Those years were marked by recessions, cutbacks in government services and the rising popularity of a neoliberal economic message that said the best way to stimulate the economy is not to help the poor but to cut taxes for the rich, Podair says.

King would have been engulfed by the white backlash, Podair says.

“He was a martyr, so even white conservatives have a different view of him now. But had he lived, they would have been saying some nasty things about him. They would have called him a socialist, a Marxist or a communist.”

Black militants were already calling King nasty names when he was assassinated. They were dismissing his nonviolent philosophy as naive, too passive. That would have continued had he survived, some say.

Images of nonviolent black marchers singing “We Shall Overcome” while getting beaten didn’t seize the imagination of many blacks anymore. But pictures of Black Panther leaders clad in leather jackets while toting guns did.

King couldn’t stop the rise of black militancy. Perhaps he could have redirected some of its energy, but too much anger was building, says Giamo, from Notre Dame.

“King was a voice of reason and moderation,” Giamo says. “As it was, with King gone, a more militant presence in the civil rights movement provoked more of the backlash that we saw in affirmative action and busing. You lost that moderate voice. You lost the center. And the center did not hold.”

He would have teamed up with Mandela — and taken on Trump

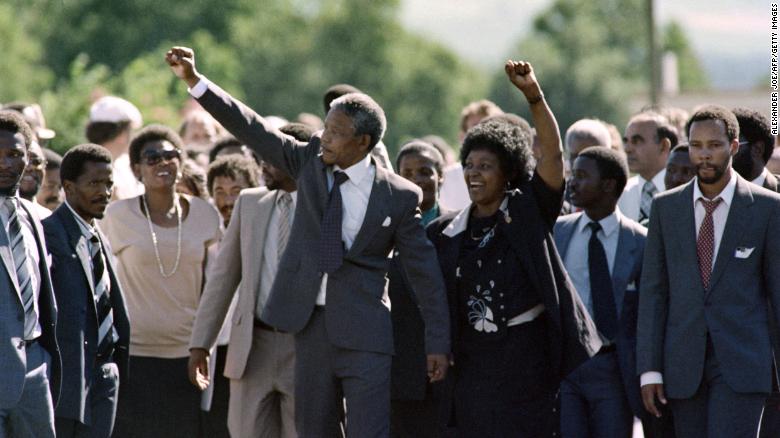

Fast forward to 1990 and imagine this scene:

Nelson Mandala has just been released from prison in South Africa. The world is about to get its first glimpse of the anti-apartheid leader in 27 years. As he emerges in the sunlight, leading a procession of supporters, Mandela thrusts his right fist into the air in a victory salute. Next to him, a beaming King, his closely cropped hair now speckled with silver, raises his fist in salute as well as they walk past cheering crowds.

This is the post-1968 scenario the Rev. Curtiss Paul DeYoung envisions for King. In his imagining, King’s moral appeal is too global to be tarnished by domestic changes in US politics. He’s a global leader who would naturally seek out another transcendent figure: Mandela.

DeYoung, CEO of the Minnesota Council of Churches, taught a college course on King and Malcolm X for 25 years. King had spoken out against apartheid, he says.

DeYoung imagines a “creative interchange” between the two men, with Mandela “reinvigorating King’s work around racism.”

“King never gave up on the humanity of white people, and Mandela brought that kind of sensitivity to whites in South Africa,” DeYoung says. “He really believed that whites could be redeemed and reconciled. He had converted enough of his jailers while he was in prison.”

Had King lived through the 1990s and beyond, how would he have responded to other social justice issues of the time, such as women’s rights and gay marriage?

For starters, DeYoung says, King — who often said injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere — would have been forced to re-examine his own private behavior.

King had extramarital affairs, a secret that was revealed through FBI surveillance.

“If he saw gender as a justice issue, it might have changed his view of women and therefore his extramarital behavior,” DeYoung says. “He would have to critique his own extramarital affairs from a justice perspective.”

King acted like many traditional black pastors of his time. He grew up in a hypermasculine, patriarchal black church where women were treated as subservient. He reflected some of that standoffish attitude toward assertive woman in his treatment of Ella Baker, a legendary civil rights organizer.

Yet on LGBTQ issues, he acted like a man ahead of his time. He rejected repeated calls to disavow Bayard Rustin, a close aide of his who was gay.

Some think King’s wife, who became a champion of gay rights, would have further cultivated that part of King.

“She understood the movement for sexual and gender equity was a civil rights movement,” says Vincent Stephens, director of the Popel Shaw Center for Race & Ethnicity at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania.

“Had he lived, she would have been able to play a positive role to help him broaden that conversation.”

Fast forward to today and imagine King in the era of President Trump.

This scenario is not hard to conjure. Some of King’s closest friends and aides — Rep. John Lewis, Andrew Young, the Rev. Jesse Jackson — are still in the public eye and weigh in on current events.

Imagine King taking to Twitter to engage in a verbal shootout with Trump.

“He would probably do quite well on Twitter because of his ability to express himself in a few words and write things that people could remember,” says Podair, the Lawrence University historian. “Trump would have given him a nickname.”

On the other hand, Podair says, maybe King wouldn’t take to Twitter. His lofty pronouncements might not play well in a world full of snark and juvenile memes.

“The Twitterverse is such a cesspool that he might say, ‘I don’t even want to get involved,'” Podair says.

There is one public battle King would not be able to resist joining — critiquing the white evangelicals who support Trump. Podair envisions a contemporary “Letter From Birmingham Jail” bristling with references to Scripture and irrefutable logic.

“He would be hitting them where they lived,” Podair says.

“They can always dismiss others by saying they don’t understand us. What King could do is say, ‘I come from the same place as you do. I can recite the Bible right along with you. I grew up in the church and I’m telling you’re on the wrong path.’ They couldn’t turn their back on him.”

He would have become an elder statesman

King could have turned his back on public life. But he may not have had the choice to step aside. He could have been forced aside by health problems, or even scandal.

Some of King’s closest friends would have “staged an intervention” and forced King to step away from his public role, says David Garrow, author of the Pulitzer-Prize winning biography of King, “Bearing the Cross.”

“By 1968, King is so exhausted and so drained physically and mentally that he’s on an emotional edge that he’s never been before,” Garrow says.

During his last days in Memphis, King told an aide that he had a migraine headache for three days because of divisions within the civil rights movement, “and sometimes I feel like turning around, just quitting, or maybe becoming president of Morehouse College,” according to “Voices of Freedom,” an oral history of the movement.

Garrow says he can envision King retiring and become an “elder statesman” in American public life.

“‘Doc’ so often over the years had always fantasized about stepping out of the public eye and just going back to being a minister and teaching a philosophy course at Morehouse,” says Garrow.

Yet there was a part of King that drove him to activism, Garrow says.

Part of that was guilt. He felt like he had to keep earning the acclaim of the Nobel Peace Prize he had been awarded in 1964. He felt that he had received too much credit and others in the movement had been ignored.

He had “this unstoppable pressure to keep sacrificing himself,” Garrow says.

“He still didn’t feel worthy of everything given to him,” Garrow says. “That’s the most unique thing about King and the thing that people find hardest to appreciate about King whenever they think of some famous celebrity type. They’re assuming that those people have some huge-sized ego. Doc had none of that.”

King actually didn’t want to be a civil rights leader, Garrow says. He was drafted.

People picked him to lead the Montgomery Bus Boycott; they chose to build the Southern Christian Leadership Conference around his persona; he was often cajoled and pressured into various civil rights campaigns.

“It’s always other folks who are taking the initiative and drawing him in,” Garrow says.

That kind of pressure took a physical toll. Some say King might not have even lived to an old age had he survived Memphis.

Randal Maurice Jelks, an African-American studies professor at the University of Kansas, says autopsy reports show King “was in pretty bad shape physically.”

“He was under constant stress and surveillance,” Jelks says. “He smoked. His liver was shot. Think of how many funerals he had to go to and do.”

Lafayette, King’s aide, says King kept a punishing schedule. He hardly ever saw him sleep.

“He’d make five speeches a day,” he says. “The person traveling with him would just be exhausted. What I would do is send another person with a fresh suitcase and clothes and they would relieve him. And Martin Luther King would keep him going.”

King could have collapsed from the weight of scandal as well.

The FBI knew of King’s extramarital affairs and, according to some, tried to induce him to commit suicide by mailing tapes of his trysts to his home in Atlanta along with a taunting letter.

Yet imagine King in a post-Watergate era, where a public figure’s private life is fair game. Imagine camera crews ambushing King.

“They would have gone after him,” says Podair, the Lawrence University historian. “God knows there might be women suing him. There would certainly be a lip-smacking satisfaction that, ‘Hey, we caught him doing that.’ … Sean Hannity’s head would be exploding.”

As grim as those scenarios may be, Lafayette doesn’t remember gloom from King’s last days in Memphis.

He remembers King’s resilience.

King wasn’t supposed to make the “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech the night before his assassination. He was in bed at the Lorraine Motel and it was pouring rain. The phone rang. An aide pleaded with King to come to the church that night to make a speech, telling him, “This is your crowd,” Lafayette says.

King joked with the aide, playfully asking if him if he was seriously asking him to get out of his pajamas, put on a suit and go out in a rainstorm, Lafayette says.

King went, and we can see the result on film: his last speech. Eyes blazing as he peered into a cheering audience, King almost seemed to be on the verge of tears near the end. He seemed to foretell his death, vowing that, even though “I might not get there with you,” “we as a people will get to the Promised Land.”

King preached himself out of his depression, Lafayette says.

“The mountaintop speech lifted him up again,” he says.

Five decades after his death, we can wonder what would have happened, had King lived. But there’s another what-if we can ask that goes back further:

What if King had never accepted the request to head the Montgomery Bus Boycott when he was just 26 years old? What if he spurned later efforts to get involved in the movement, preferring instead to move to Atlanta to take over his father’s church and live a comfortable, middle-class existence with his wife and four kids?

What if the world never heard “I Have a Dream,” no one ever read “A Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and that rich, rolling baritone of King’s had never been heard by countless desperate people across the globe who cling to King’s belief that “unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality?”

That, perhaps, would have been the greater tragedy.