https://www.illinoispolicy.org/pritzker-budget-lifts-cap-on-pension-spiking/

A provision included in Illinois’ previous budget aimed to protect state taxpayers from end-of-career salary spiking in local school districts. The budget proposal en route to Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s desk would repeal that protection.

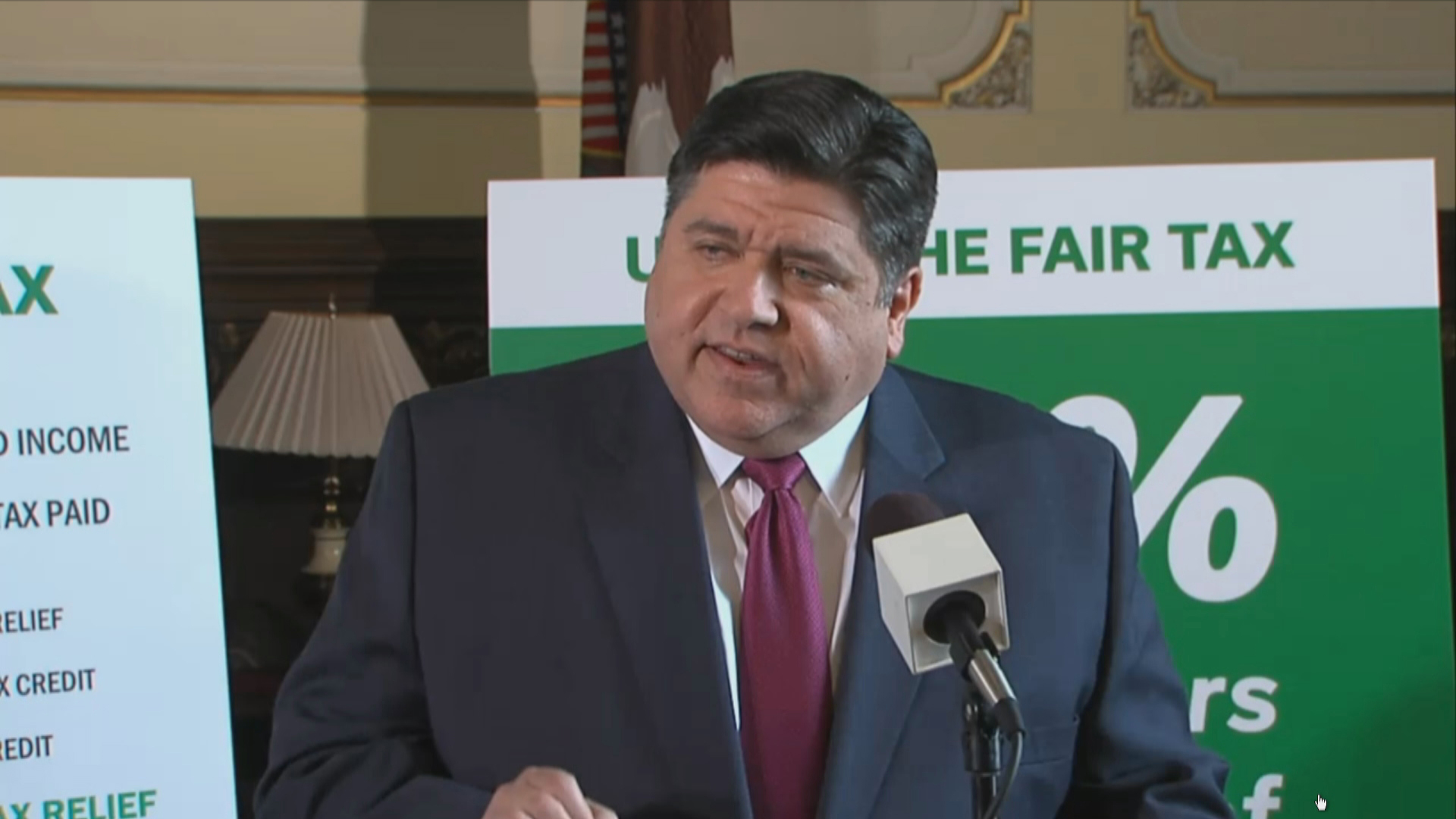

One saving grace of last year’s state budget in Illinois would be null and void if Gov. J.B. Pritzker approves the one state lawmakers have proposed for the coming fiscal year.

Included in the record $40 billion budget passed by the Illinois General Assembly is the elimination of a taxpayer protection against “pension spiking” by school district officials.

Pension spiking is the practice of boosting an employee’s salary during his or her final years of work before retirement. The Teachers Retirement System, or TRS, pension formula calculates retiree benefit levels by averaging an employee’s highest four consecutive years of salary within the final 10 years of his or her career.

State lawmakers capped end-of-career salary spikes to 6% per year in 2005. School districts were still free to hike salaries by whatever amount they chose, but increases above 6% annually meant local taxpayers would have to make extra contributions into TRS, rather than the state.

Unfortunately, school districts began treating that limit as a given, and began automatically hiking salaries by 6% each year for the four years prior to retirement. These raises massively boost a worker’s retirement benefit. Hiking a teacher’s salary by almost 26.2% means a career worker with an average salary of $73,000 will earn approximately $380,035 more during the course of her retirement when compared with 2% annual raises.

That’s why lawmakers in the fiscal year 2019 budget cut the cap in half to 3%.

But with Pritzker’s signature, lawmakers’ current budget proposal will spring that cap back to 6%.

Pension spiking punishes future teachers and taxpayers

While local school districts decide employee salaries, state taxpayers are ultimately on the hook for pension payments to TRS. That excludes the pension costs incurred by school districts spiking salaries above the cap, which the state requires school districts – or local property taxpayers – to pay. This is not uncommon: According to the Chicago Tribune, school districts across the state made a total of $38 million in penalty payments for pension spiking between 2004 and 2014.

Because wealthier school districts are more likely to have the resources to boost salaries, pension spiking forces state taxpayers in poorer school districts to subsidize those wealthier districts’ pension costs.

Some claim pension spiking is an important tool to attract teachers to Illinois. The Illinois Education Association, or IEA, went as far as stating in a press release that returning the pension spiking cap to 6% would “save the teaching profession.”

IEA’s claim is untrue. While pension spiking certainly benefits some pensioners who collect inflated retirement earnings, demanding more from a deficient TRS puts the retirement security of the vast majority of current and future teachers in jeopardy. TRS is only 40 percent funded, and holds the most debt of all five state-run pension funds, at $75 billion.

Pension spiking only adds further stress to TRS, a defined-benefit pension system that is already unsustainable.

Many school district employees would be surprised to learn that the state increased, rather than decreased, funding to local school districts over the years. That’s because required TRS contributions capture an increasing share of state education funds. Between 1996 and 2016, for example, the state increased its education funding by more than $5.4 billion, or 87%. But $3.6 billion – or 66% – of that increase went to former teachers’ pension payments, instead of current teachers’ classrooms.

Far from “saving” the teaching profession, pension spiking funnels scarce education funds to a fortunate few retirees, at the expense of teachers currently serving and future teachers still in training.

Local taxpayers also suffer. True, local property taxpayers aren’t directly on the hook for TRS benefits. But they do pay the price in a painful but overlooked way: As pensions consume state education funds, school districts must resort to hiking already-high property taxes to find needed revenue. School districts currently consume nearly two-thirds of total property tax dollars collected in Illinois.

While lawmakers would better serve teachers and taxpayers alike by working to align pension costs with school district salary decisions, there’s little doubt Pritzker will sign the budget state lawmakers worked overtime to put before him.

Illinoisans are in desperate need of property tax relief. That cannot be achieved with another task force, but only by reforming the increasingly unstable pension system in which public employees are trapped. The same state leaders who carried Pritzker’s progressive tax to the ballot with the mantra of “letting voters decide” should live up to that principle when they return to Springfield, and muster the political courage to pursue a constitutional amendment to reform Illinois’ broken pension system.