As businesses reopen across the city and state and COVID-19 infection rates have slowed, new cases in Illinois’ Latino communities have continued to climb. In fact, the total number of infections among Latino residents in Illinois is on track to comprise half of all COVID-19 cases in the state, according to the Latino Policy Forum.

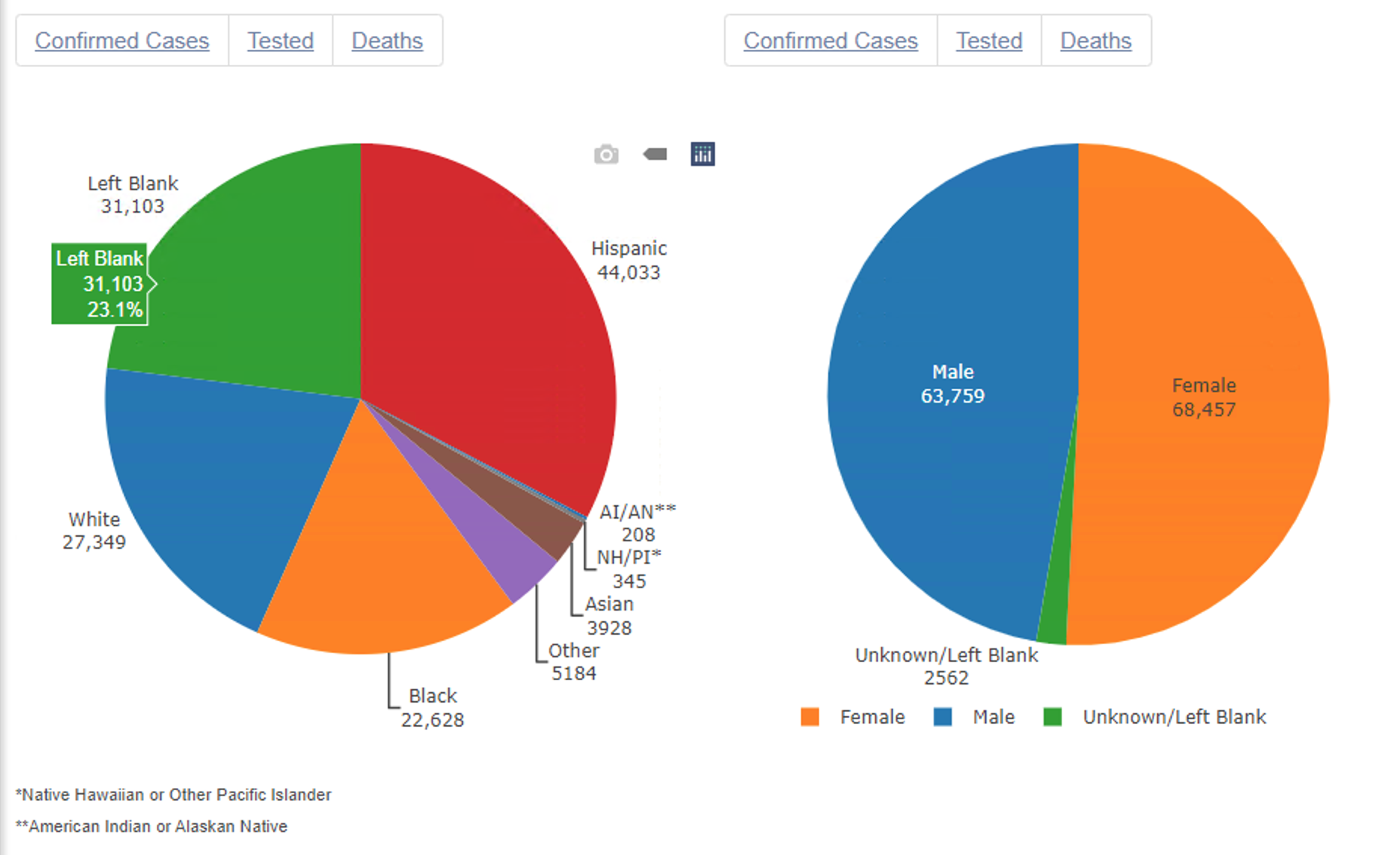

To date, more than 44,000 cases labeled “Hispanic” on the Illinois Department of Public Health dashboard account for about 33% of all cases of the virus in Illinois. Hispanics and Latinos represent about 17% of the state’s population. In Chicago, Latinos represent about 29% of the population, but account for 44% of cases per the city’s data portal.

Now, as Latino communities scramble to understand why the coronavirus has hit them so hard, they’re calling upon elected officials to do more to help reverse the trend of rising infection rates.

And there is concern that the often-incomplete racial and ethnicity data being used to track these cases is masking even greater numbers of Latino cases of infection.

According to IDPH data, as of June 18, cases in which ethnicity data was “left blank” account for more than 31,000, or about 23%, of all confirmed cases in Illinois.

(Source: Illinois Department of Public Health)

(Source: Illinois Department of Public Health)

Those working in the Latino health care community say there is good reason to believe that many of those “left blank” responses are actually Latinos.

Dr. Marina Del Rios, director of social emergency medicine and associate professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said though the numbers of infections in Latino communities are already distressing, she believes they’re still being undercounted.

“We’ve had insiders in the medical examiner’s office, for example, that have suggested there are Latino surnames that are being labeled as white or where race/ethnicity have been left undefined. There’s so many of us in the Latino community that know more than one, two, six people that have had COVID and who have been personally affected by death it’s surprising that the numbers are not worse. I hope that they aren’t but I don’t have faith that that’s the case,” said Del Rios. “Without the data it becomes very difficult to track the severity of illness in any given population. We end up using surrogates like ZIP codes, but that’s not as accurate.”

Carmen Vergara, chief operating officer of Esperanza Health Centers, said that for the Latino community, the question of reporting their racial and ethnic status is complicated. “Race and ethnicity are very complex concepts, and not everyone in the Latino community particularly agree with the categories that the government has given us to choose from.”

When it comes to electronic health records, Vergara said the “left blank” problem is threefold.

First, the race/ethnicity field on electronic health records are often poorly structured. “That race/ethnicity field is just not properly standardized with most electronic records,” said Vergara. “It was structured where patients chose race or ethnicity, and none of these vendors really worked to solve the problem … now we’re seeing some negative effects of this not being resolved.”

Second, Vergara says that race and ethnicity are complex issues and not everyone, particularly Latinos, agree with or identify with the categories that the government offers as choices. But she says health care workers are not the right people to make those determinations for patients. “You get taught quickly in the medical field that you don’t report anything that the patient didn’t report,” Vergara said.

Third, Latinos may worry about their information being reported to immigration officials. “People are questioning, is that info relevant? Who’s going to see it?” said Vergara.

People wearing masks line up for a food drive in Brighton Park on Chicago’s Southwest Side on April 23, 2020. (WTTW News)

People wearing masks line up for a food drive in Brighton Park on Chicago’s Southwest Side on April 23, 2020. (WTTW News)

Del Rios has heard anecdotal evidence that this may be the case. “We’ve heard reports of people who showed up at testing sites [getting] asked the citizenship question, and that was enough to prompt them to not identify their ethnicity.”

Vergara says the data’s accuracy is vital to health care providers and public health officials as they develop strategies for fighting disease. “We’re using that data to drive our decisions, and if we don’t have the right data, we might be making the wrong decisions,” she said.

Vergara says her organization began using kiosks that allow patients to enter their own information about a year ago in response to studies showing that patients were more likely to accurately report their demographic information themselves.

Del Rios says that understanding trends among communities is also necessary to distribute resources equitably. “If it really turns out 50% of the Latino community are the ones that are currently infected but you distribute resources by population, does that make sense?” she said.

Vergara said the state government has at least one short-term option for improving the quality of their ethnicity day. “Making that [ethnicity] field a required, mandatory field on the disease surveillance reporting system. I think that is something that’s low-hanging fruit that we could implement rather quickly.”

As to why Latino communities continue to see rising numbers of cases, Vergara believes that the primary risk of exposure is in workplaces that employ high numbers of Latinos, such as meatpacking, transportation and service industry jobs where physical distancing is difficult or impossible.

“They’re at work and at risk for exposure and their employers don’t know how to protect them or have clear guidance. The guidance is getting better, but back in April, early May, it was really lacking,” said Vergara. “So that definitely put folks at risk from the get-go in the workplace and then the secondary was taking it home to their families, and because Latinos tend to live in multigenerational households, that’s how that exposure and transmission continued.”

Del Rios agrees with Vergara’s assessment. “Physical distancing is a privilege that marginalized people do not have. The reason Black and Latino communities have been so disproportionately affected is that physical distancing is not possible for a lot of us, especially when you live in a multigenerational home or you have to continue working in sectors like transportation, food preparation, or health care.”

Though Vergara believes that the best time for action was back when the first cases appeared – “it all goes back to the lack of a national testing strategy,” she says – state officials should now concentrate on getting funding where it’s needed, and then get out of the way.

“There’s a lot of funding that has been announced, so I think sending that out quickly without any restrictions, just letting folks do the work, let them start hiring people and getting them trained to do the work that needs to be done over the next six to nine months as soon as possible,” she said. “Often there’s a lot of red tape for grants and administrative paperwork, and if we don’t have to deal with those headaches and just let us do the work, I think that would go a long way.”