Photo by Ronnie Wachter

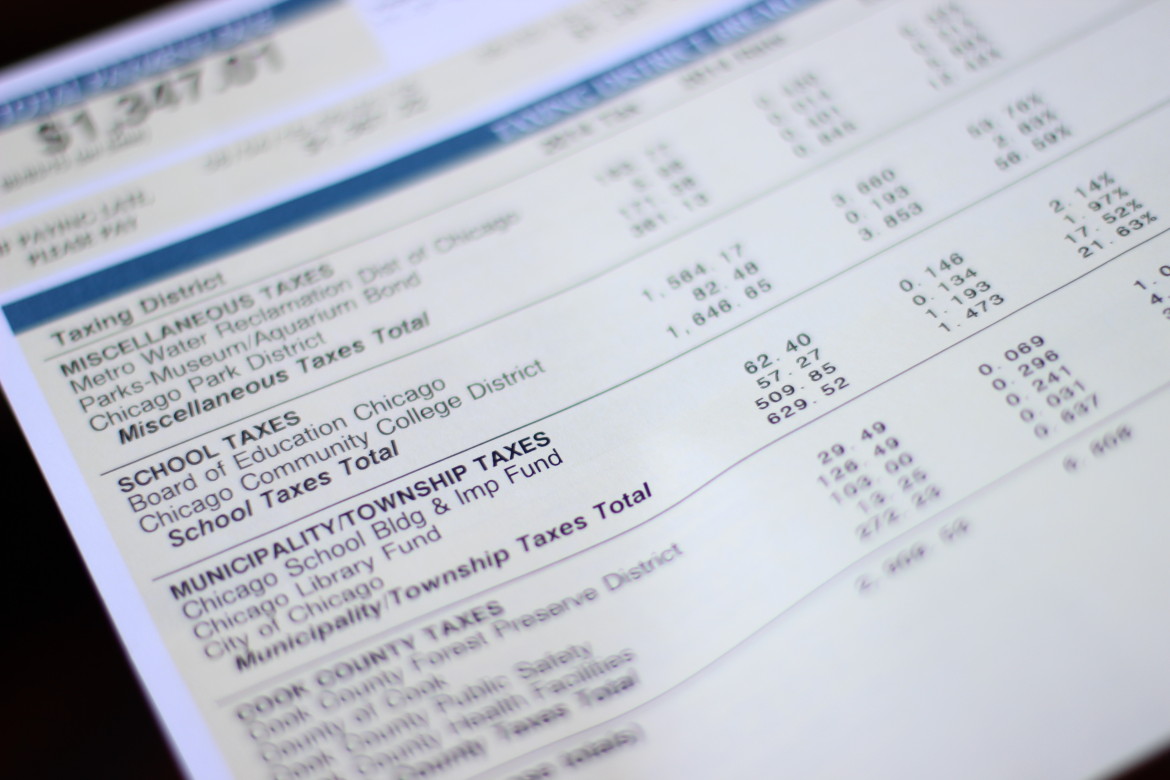

Cook County homeowners deserve property tax relief (Chicago Reporter)

|

Mayor Rahm Emanuel has proposed a new exemption that would shield homeowners with properties worth $250,000 or less from his looming property tax increase—if Gov. Bruce Rauner agrees to back it, which doesn’t look likely at this point.

Some Emanuel supporters have argued it would be hard for Rauner to oppose tax relief for homeowners. But as statements from the Governor’s office have underscored, it’s tax relief for some and but a tax increase for others—particularly commercial property owners.

Of course, as with everything related to the property tax, it’s more complicated than that. The fact is, it would take a huge homeowner exemption to restore the balance between residential and business property owners. For over 30 years, the tax burden has been steadily shifted onto homeowners.

It’s an issue James Houlihan raised when he was county assessor and advocating for a tax cap. The Chicago Political Economy Group discussed it earlier this year in a report outlining a progressive economic plan for the city.

Using data from the Illinois Department of Revenue, CPEG’s report (see figure 4) shows that the share of Cook County property taxes paid by residential owners has climbed from 44 percent in 1981 to 62.7 in 2012, while business owners’ share dropped from 55 percent to 37 percent.

To some extent that shift reflects the growth of residential home values; but that just underscores what a blunt instrument the property tax is. Because while home values have risen, incomes for most people have stagnated or fallen. Increasing home assessments—especially during a housing bubble—don’t reflect homeowners’ ability to pay.

On the other hand, commercial and industrial buildings are assessed, in part, based on the income they produce. (Those buildings are doing very well for their owners, with rents at top-tier downtown office buildings up by almost one-third in the past year alone.)

What’s remarkable about the shift is how inexorable it’s been, through housing booms and busts, despite tax caps and exemptions instituted over the years to protect homeowners. Every year a little more of the tax burden moves from businesses to residents. The proportion paid by Cook County homeowners increased by 11.3 percent from 2001 to 2010—while the county lost 182,500 residents.

According to Ron Baiman of CPEG, figures from the past decade show that the shift in residential tax burden far outpaces increases in home values. What could account for it?

If you guessed the “notorious insiders’ racket” of Cook County property tax appeals, you’re on to something. That’s the system where owners of big downtown commercial buildings hire politically-connected law firms—like Ed Burke’s and Mike Madigan’s—to get their assessments reduced; those property tax lawyers fund the campaigns of the officials they deal with. (Cook County is one of the few counties in the state with an elected assessor and Board of Review. Maybe that’s not such a good idea.)

According to the Chicago Lawyer, from 2007 to 2014, reductions of commercial property assessments by the county’s Board of Review were five times greater than reductions of residential assessments. And according to a Civic Federation report, from 2000 to 2008, the assessor’s office and the Board of Review reduced residential assessments by $4.85 billion and commercial assessments by $32.5 billion—almost seven times more.

Every case the lawyers win means higher taxes for homeowners, and it adds up. “When you have a group of property owners who are consistently, year after year, pursuing appeals and getting reductions, you end up with a shift of the burden from one class to another,” Ares Dalinium, an attorney who represents school districts challenging assessment reductions, told the Chicago Lawyer.

The Progressive Caucus has proposed an alternative minimum property tax for the central business districtin order to reduce the pressure on the city budget from “tax giveaways” won by “political insiders.” The city would set a minimum valuation on property for tax purposes that would bring in tens of millions of additional dollars, possibly much more. It’s a proposal that should be on the table in case Emanuel’s exemptions don’t fly in Springfield.

Something the city could do right now, according to Ald. Scott Waguespack (32nd Ward), is step up challenges to property tax appeals by large downtown buildings. Taxing bodies can intervene if property owners appeal Board of Review decisions to the state Property Tax Appeal Board, but the city’s law department rarely does—typically filing about a dozen undervaluation cases a year, a small subset of downtown properties seeking reductions, the Chicago Lawyer reports.

Part of the problem is a 2002 ordinance backed by Burke which bars the city from intervening in appeals seeking assessment reductions lower than $1 million. In 2007, according to the Sun-Times, Burke handled an appeal on a Loop building owned by AT&T, avoiding intervention by the city by asking for a reduction of $999,999. It may be time to revisit that ordinance.

Without intervenors, hearings at the state board are cursory and property owners win, Waguespack said. “When you talk about major inefficiencies in the city, this is one place—the fact that they’re not contesting the major portion of these buildings that are getting tax breaks,” he said. He’s urged the city to increase staff dedicated to challenges.

The Progressive Caucus also called on the mayor to provide exemptions based on income levels rather than home values. This is a particular concern of Ald. Carlos Ramirez-Rosa (35th Ward), who represents Logan Square, where incomes have not always kept up with soaring property values.

With Emanuel proposing an exemption for homes valued under $250,000, “what really frightens me are longtime residents, seniors living on a fixed income, whose home is valued at $500,000 but who are struggling with their current taxes and cannot afford a $1,000 increase,” Rosa said. He’s afraid it will lead to an increase in predatory tax auctions, which he calls “a very nasty process.”

Rosa is preparing an ordinance that will provide a rebate for homeowners based on their income levels. Ald. Joe Moreno (1st Ward) has a similar measure, but Rosa says his ordinance will provide much larger rebates. The key point, perhaps, is that the city can enact this on its own—as Mayor Daley did in 2009—without state legislation.

If Mayor Emanuel is serious about protecting moderate-income homeowners, this option needs to be on the table.

The bigger issue—and the reason property taxes are indeed so high on residents of Illinois and owners of downtown office buildings—is the overreliance on property taxes in a state where the revenue structure is highly regressive. That’s not part of this debate, but someday it will have to be.