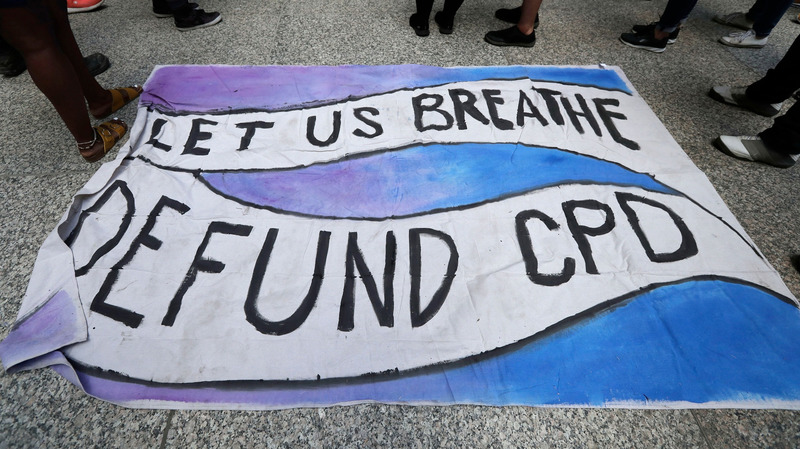

A sign is seen outside of Federal Plaza during a protest in Chicago over the death of George Floyd. Floyd’s death is bringing greater attention to the “defund the police” movement in Chicago.

Nam. Y Huh/Associated Press

No one in Chicago’s black neighborhoods wants police killings or police brutality. That’s a given.

Beyond that, black Chicagoans have varying ideas of what constitutes good policing.

When the looting took place on parts of Chicago’s South and West sides earlier this month, different responses emerged out of black neighborhoods. Some thought more police officers should have been in those communities as a form of protection. Others did not.

George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police is bringing greater attention to the “defund the police” movement in Chicago, inspiring a slew of protests of the same name. Floyd’s death shook loose raw emotions that black Chicagoans have too often felt, when black people here were killed by police. For a decade, Chicago activists emphasize that police reform isn’t enough. They want to defund the Chicago Police Department.

However, as calls to defund police gain traction, the concept may require a closer look in Chicago’s black communities due to their unique relationship with police. While black Chicagoans have been the most notable victims of police violence — their names often evoked during defund police protests — black communities have also established strong partnerships with police. Block club members and residents in black neighborhoods may not trust the police, but they work with them because of public safety concerns.

The language is intentional and isn’t new here, yet “defund the police” is still a mystifying term for many. But, in short, it means taking money from a police department that is 40% of Chicago’s city budget and reinvesting in other under-resourced areas like public education.

South Shore resident and Movement for Black Lives organizer Charlene Carruthers said the possibilities are endless: “fully funding quality public mental health care services for everyone, affordable and free housing.”

Activists also question whether sending armed police officers is the most appropriate response to situations that involve social issues, from homelessness to sexual assault, to domestic disputes, to mental health episodes.

Northwestern University sociologist Mary Pattillo has studied black Chicago neighborhoods for 25 years. Pattillo says that the relationship between black communities and the police is complex because the people in those communities are complex by socioeconomic status, homeownership rates, gender and age.

“And that complexity within the black community leads to multiple experiences and thus positions about the usefulness of the police and how much police we want,” Pattillo said.

In Chicago’s black neighborhoods — regardless of income — residents often engage with police at beat meetings and the like. They work within the system handed to them. Pattillo has attended her share of those types of meetings. She’s witnessed residents demand better city services — and that includes demanding better policing.

Despite those relationships, black residents harbor doubts. Policing in this country has roots in slavery and protecting white property. White people who call the police on people for living while and being black takes a toll. According to the CATO Institute, 68% of white Americans have a favorable view of the police.

For black Americans, it’s 40%.

That’s still a sizable number with a favorable view, Pattillo said. The relationship is also complex because of what else is happening in black neighborhoods.

“Everything from lack of jobs and how that lack of jobs leads to burglaries and personal robberies and those community-level problems are things that we then need protection from as well. We also know, even as victims, we aren’t often treated with respect and dignity that victims should be treated with,” Pattillo said.

Carisa Parker is a Washington Heights resident who routinely engages with police officers through her neighborhood volunteerism. Her 20-something-year-old son is now a police officer, so she formed a group of black women who are mothers to Chicago police officers to help foster community partnerships. She also appreciates the presence of police officers at Morgan Park High School, where she is president of the local school council.

“At Morgan Park, we love our police officers. They’re an extension of the Morgan Park family. They’re not just there to police; they’re there to counsel and support. I see them talking to kids all the time,” Parker said.

But Parker recognizes the shortcomings of police interactions. After reporting that intruders had broken into her home, she never heard back from the detective. She wants beat officers to get out of their cars and walk the blocks to know neighbors. Still, Parker believes the department can better serve black residents.

“If we want to see change and healing in the police department, the police who patrol our neighborhoods need to look like us. They need to be culturally competent. They need to understand the issues that we’re faced with. And if you have somebody who looks like you, who grew up like you, then you’ll have a better job of trusting,” Parker said.

A few miles northeast, Darlene Tribue has led Park Manor Neighbors Community Council for 32 years. She said she’s seen police commanders come and go — good ones and bad ones.

“We voice our complaints and everything, and most of the time they listened to the community because if they didn’t, we would gangbuster them in meetings,” Tribue said.

Residents exert pressure — often around patrolling and police response times to actual crimes. Relationship building is key, she said. But Tribue added that while many neighbors don’t trust the police, they still want to feel safe. Personally, there are some officers that she trusts, yet there are others that she doesn’t.

“By being a senior community, they need to have help,” Tribue said. “In some cases, where they’re being robbed and somebody’s breaking in their house and they’re living alone, if they pick up that phone and call 911, they need help.”

“I don’t want to look at a time and we can’t get police response for a major issue,” Tribue said.

Activist Carrathuers said that policing in its current form is all we’ve known, so it seems like the only option for communities. And that’s what residents like Tribue are used to.

“We also need more people at the table to figure it out. That’s the invitation right now. But we can’t get there if we’re stuck on: we can’t survive without the police,” Carruthers said. “We have to get beyond that place and say, ‘What do the police actually do?’ ”

“They do stuff like car accident reporting. We don’t need the police to do that,” Carruthers continued. “Being the ones to direct traffic. We got people downtown everyday who direct traffic without guns. There are so many things police are funded to do that we don’t actually need them to do. And if that’s where we need to start, I’m down to start there.”

Tribue is down, too. Defunding the police is still a foreign concept to her. When society opens up more and in-person community meetings resume, she said she welcomes learning more and listening to organizers like Carruthers.

Natalie Moore is a reporter on WBEZ’s Race, Class and Communities desk. You can follow her on Twitter at @natalieymoore.

© 2020 WBEZ Chicago