Info Shared by Linda:

Disinvestment in Black and Latino Chicago neighborhoods is rooted in policy. Here’s how these communities continue to be held back.

It’s an oft-quoted statistic: White families have significantly more wealth than nonwhite families in America — nearly 10 times that of Black families. The racial wealth gap continues to greatly impact the differences in opportunity and access, from long-term health outcomes of a global pandemic, to education and income levels, to what happens when a business doesn’t make enough money.

Wealth inequality exists primarily because of legal federal and local policies that prioritize white wealth, says Darlene Hightower, vice president at Rush University’s community health equity office. “When you’re thinking about why white wealth is preserved and protected and Black wealth isn’t, I think it’s just our origin story, like in a superhero movie,” she said. “I think our country has an origin story and it is built on racism, racist policies, oppression and white privilege. It’s an origin story we can’t seem to get beyond.”

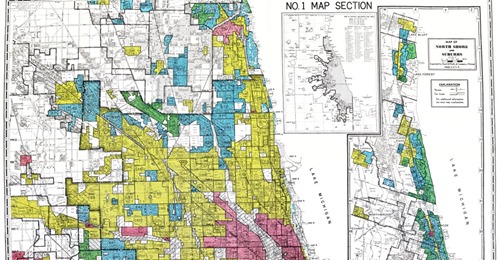

Racially restrictive covenants, which eventually made redlining possible, started appearing in private property records in the late 1800s to exclude nonwhite people from buying or renting buildings, homes and apartments, according to Kirsten Delegard, cofounder of the University of Minnesota’s Mapping Prejudice Project. The restrictive covenants were made popular by the real estate industry at a time when real estate agents felt it was their ethical duty to preserve racial homogeneity.

One of the earliest examples of a racially restrictive covenant found in Minneapolis states, “premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.” These covenants were later used to indicate which areas of a city were safe and which were hazardous — real estate agents making maps would describe nonwhite neighborhoods as “infiltrated” by Jews, Asians or Black people, drawing red lines around them to mark them as undesirable — redlining.

While these covenants are no longer legal, largely due to the opposition and work of the NAACP and Black activists, their effects linger. Today, segregation in Chicago is distinct, and most metrics of stability in which there is a large gap between Black and white populations — homeownership, education, health access — can be traced back to redlining. In 2017, for example, Chicago had higher than a 30 percentage point gap between Black and white homeownership, according to a report by the Urban Institute. Delegard attributes gaps in homeownership to intergenerational wealth transfer, which is only possible if you were allowed to own a home at all.

“Most white people have no idea that the gap is that large,” said Delegard, “and they think it’s growing smaller when in fact it’s growing larger.”

Throughout American history, Black and Latino neighborhoods, including in Chicago, have witnessed disinvestment. The severe outcomes of this are shown in a series of charts below.

Education

By 1970, the Great Migration brought an influx of Black people to Chicago. Chicago leaders, however, did not integrate Black students into majority-white schools. Instead, they were sent to school in shifts, or by mobile classrooms, called “Willis wagons.”

“When they were protesting in 1963, it was a desegregation protest but the things that people were chanting were like, ‘What do we want? Books! When do we want them? Now!’” said University of Illinois at Chicago history professor Elizabeth Todd-Breland. “These were young people saying, we’re entitled to new textbooks as well; we shouldn’t have things that are falling apart.”

There remain Chicago Public Schools policies that continue the ideas behind redlining, though less explicitly, said Chicago Teachers Union researcher Pavlyn Jankov. Jankov referred to certain policies he said have been harmful: The School Quality Rating Policy, which ranks schools by testing results; the student-based budgeting policy, which awards funding to schools based on enrollment; the proliferation of charter schools in Black neighborhoods, which privatizes education and prioritizes expansion. According to his 2017 research on segregation in CPS, the Black student population has dropped from close to 60% in 1981 to less than 40% in 2015.

“When you have schools and communities that are disinvested, you have students leaving these schools, and you have schools that end up in a death spiral of declining enrollment and resources,” said Jankov.

Food and transportation

Disparities run through the veins of Black and Latino communities, so much so that two Chicago neighborhoods, 9 miles apart, have the largest life expectancy gap in the country — 30 years, according to a 2019 NYU School of Medicine analysis. Englewood residents live to be 60 years old on average, compared with 90 years for those who reside in Streeterville. Food insecurity in Chicago’s South and West side communities continues to negatively affect health, education and economic mobility, according to the Greater Chicago Food Depository.

Decadeslong racial segregation and disinvestment are behind these food desert communities, says Daniel Block, professor of geography at Chicago State University and an adjunct professor of preventative medicine at Northwestern. “There’s racism there, but it’s also going through this deeply set system of investment that refuses to invest in these communities because homes are not well valued and people aren’t seeing the possibilities, banks aren’t willing to take a risk,” said Block, who also serves on the Chicago Food Policy Action Council board.

West Garfield Park is one such food desert in Chicago, where public officials continue to try to lure food retailers, but when they get one, another retailer leaves the area. Parts of South Shore had been designated a food desert before a grocery store opened in December on the vacant site Dominick’s left when it closed six years earlier.

“People’s everyday lives in segregated, poor, Black communities, they have to go to multiple stores in multiple neighborhoods just to feed their families,” Block said. “If we can learn how to bring more investment, but investment that is somehow locally controlled somewhat so that we don’t just bring more investment in and immediately see gentrification, then we can really start to improve things.”

This issue feeds into another area of inequity — transportation. In Chicago, eight of the 10 ZIP codes with the highest percentages of people without cars are on the South and West sides, which means a heavy reliance on public transit. (Research found Black Chicagoans lose about one week more to commuting time annually than white residents.) Deloris Lucas, an activist in the Golden Gate neighborhood in the city’s Riverdale community area, said the South Side’s transportation problems have been overlooked for years.

University of Illinois at Chicago’s Urban Transportation Center has been working with the municipalities of Dolton and Riverdale on their rail crossing issues, says UTC’s director, P.S. Sriraj. Dolton especially is burdened with about 10 grade crossings within a 1-mile length, he said, making it difficult to get in and out of those communities, with an average wait time of 15 minutes.

“Everyone that I’ve been talking to is very much aware and sympathetic to the needs and equity issues that are still very much present in society, in the Chicago area,” Sriraj said. “It’s not just going to work, it’s going to doctor’s appointments, going to get food … transportation is the great equalizer.”

The more multimodal public transportation is, he said, the more ways mobility serves the needs of the people.

“This is the time when we can introduce and explore new ideas, such as the Divvy experiment being integrated into the CTA Ventra app. There should be more of that. But they need to germinate now, in order for them to benefit the industry and communities in the long run,” he said.

Hospitals and clinics

The inequities in access to health care have not only been maintained, but have gotten worse, said Dima Qato, an assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacy Systems, Outcomes and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

“Most of the areas that are in need don’t even have primary care facilities,” she said, adding that because a significant portion of the population on the South and West sides are primarily insured through Medicare and Medicaid, it doesn’t encourage new clinics to open because reimbursements will be low.

“Our pharmacy desert closure data shows it’s actually getting worse in Black communities in Chicago,” said Qato, who has extensively researched pharmacy access for years. “When pharmacies close most of them close on the South Side, which is an area that is already underserved. And I think the same for the clinics.

“I guess that raises the question then on (federally qualified health centers), why aren’t there enough?” she said, adding that these centers would be able to get funding from the federal government to open in areas that are medically underserved. “I think it’s an important question to answer and it could be some politics, it could be some priorities — of who’s willing to open where — but there needs to be a shift.”

Areas designated by the government as underserved need to be updated to more accurately reflect the needs and differences of the local populations throughout the various neighborhoods, Qato explained. Where Medicaid and Medicare patients are being told to go for services could also be a part of the issue.

“People that are insured through public funding are not necessarily always encouraged to go to their local clinics, or hospitals, or even pharmacies, because they’re part of a network where they’re told (in order) to pay less, you need to go here, and if you go out of network, you pay more,” said Qato. “So what does that do to local clinics, businesses and pharmacies? They end up not able to sustain themselves and they close.”