“I need a whiteboard,” said Aditya Mansharamani, a junior at Adlai E. Stevenson High School, as he walks from his work station inside a mechanics lab scanning for a place to diagram one piece of an engineering project before the class period ends.

“There’s a whiteboard right here,” one classmate responded, pointing to a pile of blank sheets lying beside their table.

“No,” said Mansharamani, picking up a blue dry-erase marker and heading toward one of the room’s ceiling-high glass windows, “a bigger one.”

Mansharamani and hundreds of other students at Stevenson are enrolled courses through Project Lead The Way, a nonprofit organization offering a series of hands-on Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics (STEM) programs used in middle and high schools nationwide.

Stevenson High School junior Aditya Mansharamani diagrams part of an engineering project on his classroom’s ceiling-high glass window. (Matt Masterson / Chicago Tonight)

More than 2 million students have participated in Project Lead The Way throughout the country over the past two decades.

Last year about 1,300 high school students completed the project’s college- and career-readiness credentialing program, run in conjunction with The College Board. More than 60 of those came from Stevenson – the highest total for any individual high school in the country and third-highest total among all participating school districts.

Once completed, that credentialing can then be submitted to colleges and universities as part of their application process.

Project Lead The Way is in its fifth year at Stevenson High School, a public school of about 4,000 students located in Lincolnshire, a wealthy suburb located about 30 miles north of Chicago.

Despite its size, the school maintains a roughly 15-1 ratio of students to teachers, and is regularly ranked among the top STEM and overall high schools in Illinois.

There more than 400 students enrolled across five separate courses spanning from the basic principles of engineering up to a capstone design and development course where students spend a year working to solve an open-ended engineering problem of their choice before presenting their findings to an outside panel for review.

Because of the demand, those class sizes tend to veer more toward 25 to 28 students per teacher.

“We’re packed,” said Wendy Custable, Stevenson’s career and technical education director, during a recent tour of the school’s STEM labs.

“That’s used eight periods a day,” she said, pointing to a principals of engineering classroom while standing behind a glass wall in an adjacent lab. “This room is used seven periods a day and then we’re still having to go to other places in the school.”

Stevenson officials say they’ve spent millions expanding STEM labs inside their schools, like this one featuring a half-dozen 3-D printers. (Matt Masterson / Chicago Tonight)

The program says its alumni have a higher collegiate GPA on average than other first-year college students and are 5 to 10 times more likely to continue studying engineering and technology. Eight of 10 PLTW grads also completed four years of college-prep math courses and 97 percent of alums said they planned to pursue a four-year degree.

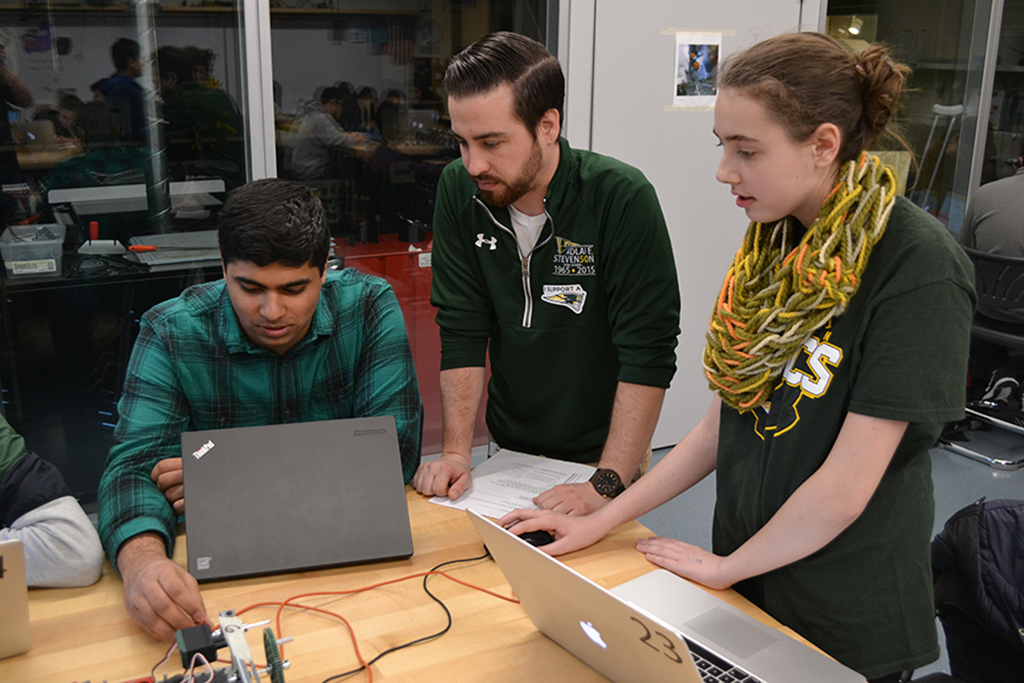

“I definitely want to continue with engineering,” Stevenson junior Abby Starr said. “Personally, I’d like to go into mechanical engineering. I’ve been involved in robotics for a really long time and I just like building things and working with my hands.”

Starr and Mansharamani are working together on a semester-long project this spring to build a working elevator scale model. Starr said the project, which stands about 3 feet tall, is about a quarter of the way finished.

The two of them will not only construct the model, but code it so the elevator car correctly stops at each floor.

Mansharamani said his favorite class within PTLW has been digital electronics, which he got into after participating in a robotics club in middle school.

“It wasn’t competitive, we were just messing around,” he said of that club. “But I thought that was really fun. So when I came here I got interested, first in the applied arts department, like web development and game development. Then through the recommendation of a teacher, I joined the robotics club here and took the PLTW courses.”

Portions of the PTLW curriculum are also used in about two dozen Chicago Public Schools, including Level 1+ schools like Lindblom Math and Science Academy and Von Steuben High School. The program has also partnered with University of Illinois campuses in Chicago and Urbana-Champaign.

The roughly 50-minute class periods are spread out throughout each school day at Stevenson and some students are enrolled in more than one PLTW course at a time. But sometimes even that’s not enough.

“I have this class scheduled,” Mansharamani said, “but I usually come in here during my lunch and either I work on this robot or I work on any project … I know a lot of other students come either in the morning or during their free period.

“They have teachers in here every period.”