A proposed bill would look into fifty strangulation cases in the South and West Sides

PUBLISHED ON

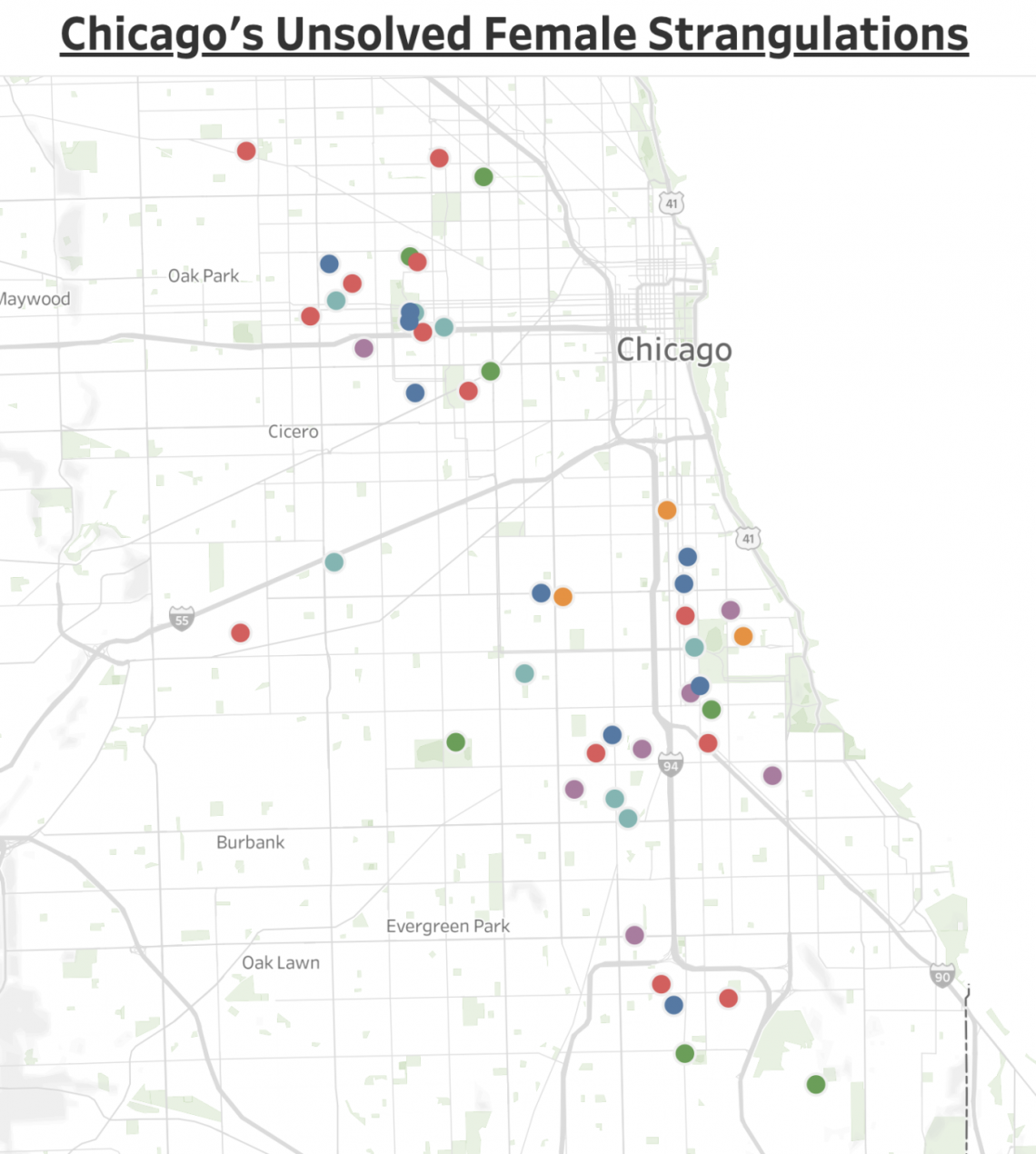

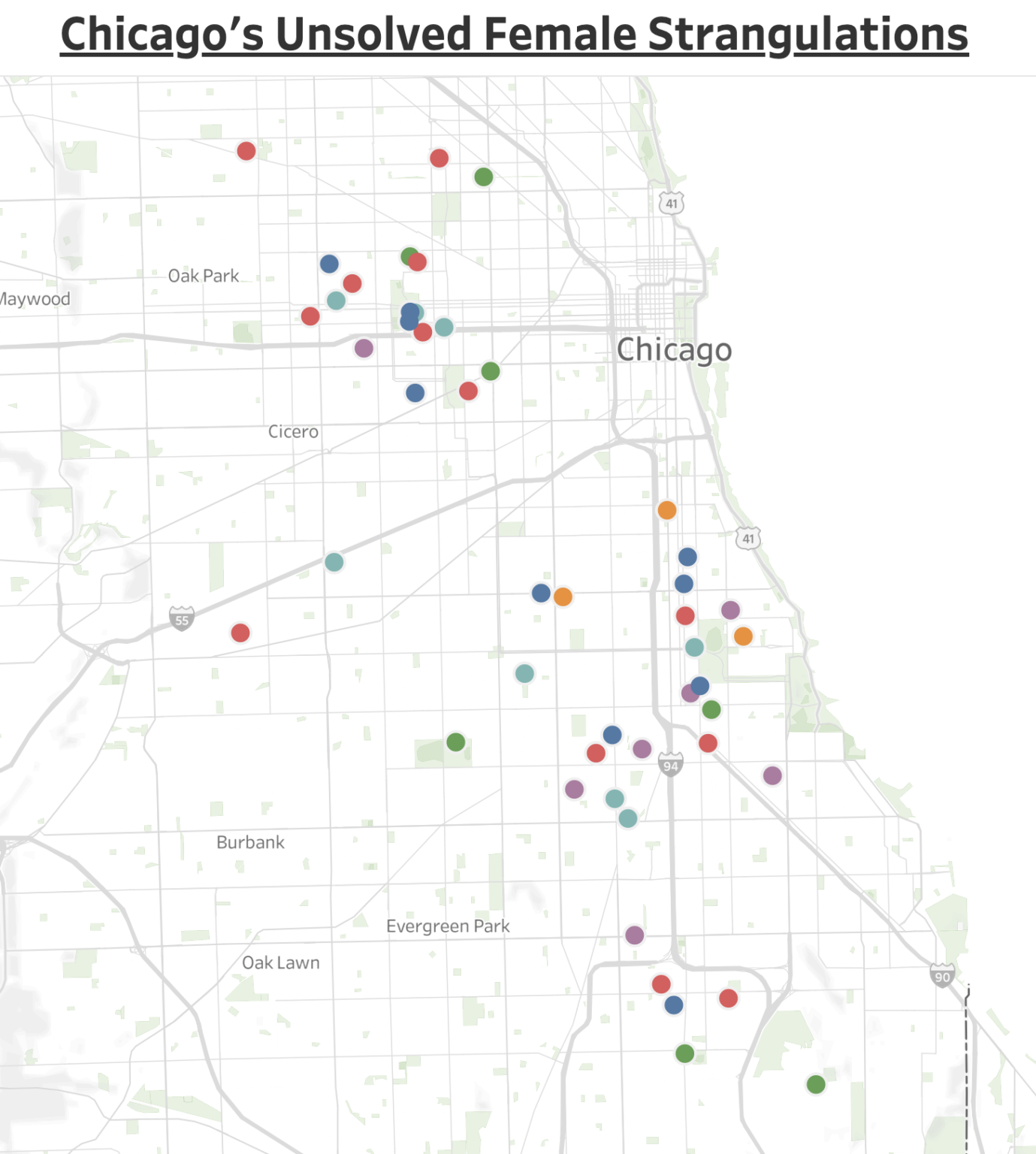

Thomas Hargrove, a retired investigative journalist, felt something was suspicious as he analyzed Chicago homicide data in late 2014. He identified several eerie patterns among a cluster of fifty-one unsolved female homicides: most of the victims had been sex workers or drug users, ninety-three percent of the murders occurred outdoors or in abandoned buildings, the murders were concentrated on the city’s South and West Sides, and in every single case, the cause of death was asphyxiation or strangulation.

Hargrove had developed a computer-based algorithm that used homicide data to flag potential serial killers. “The Chicago case could not have been more classic,” he said of the murders, which date back to 2001. After analyzing FBI data and archived news stories, the evidence became undeniable to Hargrove. Those fifty-one women were not killed by fifty-one separate men, he said: “Most of these [women] were killed by men who have killed [other women] before.”

Shortly after discovering the Chicago cluster, Hargrove founded the Murder Accountability Project, a nonprofit investigative group that tracks unsolved homicides in the U.S. Hargrove presented the Chicago data at the 2017 Investigative Reporters and Editors conference, which galvanized a flurry of media attention from the Chicago Tribune, Vice News and CBS Chicago. The media coverage, along with a report released by the Murder Accountability Project, prompted the FBI and CPD to form an investigative task force in 2019.

But only the case of Diamond Turner, who was murdered by Arthur Hilliard in 2017, has since been closed.

A dearth of DNA evidence makes these murders uniquely difficult to solve. Only eighteen of the fifty unsolved homicides yielded DNA samples, which is unusual for physical crimes like strangulation and asphyxiation. “The fact that there is such a low rate at which DNA has been obtained is suggestive,” Hargrove said. “It’s possible this killer or killers are pretty intelligent and are aware not to leave their DNA behind.”

The obtained DNA samples complicate the theory of an active serial killer. None of the samples match the DNA profiles of known criminals in the FBI’s database, nor do they cross-match to each other, a CPD representative said in an email. “At this point, there are no links or matches to a common offender,” the representative wrote. “We will use every resource at our disposal to analyze the case data and work with advocates to ensure that victims receive the justice they deserve.”

Hargrove said confidential information provided by witnesses has led CPD to believe there are two or three active serial killers, but CPD declined to corroborate this.

CPD could have used this information years ago, but the Illinois State Forensic Lab didn’t finish analyzing the DNA samples until 2019 due to massive backlogs. Miscommunication between labs and the court system; improper training of police officers, attorneys, and judges; equipment procurement issues; underfunding, and understaffing all contributed to the backlog, according to a 2020 report from the Governor’s Forensic Science Task Force.

Carrie Ward, the executive director of the Illinois Coalition Against Sexual Assault and a member of the task force, said issues at the lab caused a backlog of sexual assault testing kits as well. “There are storage rooms that have kits on top of kits on top of kits,” she said.

Ward fears that cases involving sex workers may sit longer than others because they often lack resources to advocate for themselves. “Sex workers are a vulnerable population, and depending on what their connections are, they may not have a lot of support to help move a case forward,” she said.

Though the lab reduced the backlog by thirty-three percent, according to an official press release, “We worry about statutes of limitation for reviewing information,” Ward said. “We don’t think any survivor should have to have their case thrown out because of timelines that weren’t met through no fault of their own.”

Sex workers often assume aliases and live transient lifestyles, so it’s hard to pin down who they saw last or where they were leading up to the murder, and distrust for the police makes sex workers reticent to cede information.

The pandemic has delayed passing legislation that might expedite the investigations. Slightly over a year ago, Illinois House Rep. Kambium Buckner introduced the Task Force on Missing and Murdered Chicago Women Act to the Illinois General Assembly. The bill, which would study the causes behind Chicago’s murdered and missing women and increase awareness of sexual assault, was on track to be enacted into law. But when the pandemic hit, the General Assembly ceased to congregate.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has posed challenges to sex workers and survivors of assault. COVID-19 shuttered services available to survivors of sex trafficking, the city’s stay-at-home order has sequestered victims at home with their abusers, and unemployed people may be turning to sex work—a field that makes them particularly vulnerable to sexual assault.

Sex workers are frequent targets

One night in the late nineties, Lynette Frazier (a pseudonym), was selling sex in Chicago’s Gold Coast neighborhood. She was picked up by three men who strangled, beat, and raped her behind a building near North State Street and West Delaware Place. CPD officers happened to be nearby and managed to catch one of Frazier’s assailants, who had stolen her wallet, ID, and cash, which the officers used to corroborate Frazier’s story.

The attacker was jailed and faced felony battery and theft charges, but felony charges in Illinois must be reviewed by the state’s attorney. Frazier said the Office of the State’s Attorney declined to charge the man with a felony because Frazier was a known sex worker. Instead, she said he received a misdemeanor assault charge. To Frazier, the incident solidified her mistrust of the criminal justice system. “In that day at that scene, I knew they weren’t going to do anything,” she said.

If there are killers targeting sex workers in Chicago, it’s likely some victims have survived the attacks and could serve as key informants, Hargrove said. But like Frazier, many sex workers have reason not to go to the police. According to a January 2020 report produced by the Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation, sex workers in Chicago have largely reported negative interactions with the police.

“Folks in the sex trade are not treated well by police, and that’s putting it lightly,” said Madeleine Behr, the Alliance’s policy manager and author of the report. “It’s not only discriminatory comments, derogatory comments or verbal harassment, but escalating all the way up to sexual assault and abuse and using the badge to do it.”

Sexual misconduct is the second most common form of police misconduct, according to the Alliance’s report.

In addition to sexual misconduct, Behr identified several factors that undermine relations between sex workers and law enforcement. CPD tends to enforce prostitution laws against those selling sex rather than those buying sex or trafficking, which assigns guilt to sex workers. In 2017, ninety-one percent of prostitution arrests were for selling sex, according to the report, and this portion has only grown since the Alliance began to collect data in 2013. Behr said this is likely because sex workers are more visible than johns or pimps, and because male police officers identify more with men who buy sex “or a trafficker, especially if it’s a white guy, someone that they probably can relate to.”

Paul Olson, a retired Cook County Sheriff’s officer, said some of his former colleagues eschewed arresting johns. “Some guys had the attitude of, ‘If I arrest this guy it’s going to ruin his life, his wife’s going to find out,’” he said.“[The police] are driving around, they see a girl they know is a prostitute and they just put a case on her for soliciting even though they didn’t catch her doing anything.”

Olson retired from the force in 2008, but Behr said this phenomenon still occurs. While interviewing former sex workers for the report, Behr heard stories of women who were arrested after leaving the sex trade because the police recognized them. “They spoke about being fearful to do everyday activities in their neighborhoods because of it,” Behr wrote in an email.

Behr believes victim blaming—the belief that sex workers are responsible for their trauma—is also at play. “We as a society are more comfortable blaming people for their circumstances, rather than holding men, particularly white men with power and privilege, properly accountable,” she said.

Brenda Myers-Powell, co-founder of the Dreamcatcher Foundation and a former sex worker, said, “The police treat us with no dignity and no respect. If somebody rapes you or hurts you, it’s your fault. You shouldn’t have been out there.”

Mahoganey Harris, another former sex worker, rarely reported men who attacked her for this reason. Around 2011, Harris had a violent brush with a man she believes had killed another sex worker. She had heard of a sex worker who was strangled to death, the skin of her assailant still under her fingernails when she died. Less than a week later, Harris found herself in a hotel room with a man who was covered in fresh scratch marks. The man tried to lock Harris in the room so she fled unclothed to the hotel lobby. The hotel employees were skeptical of her story, and even more so when the man claimed Harris had stolen money from him (she didn’t). Harris never reported the man to the police and doesn’t know if there was ever an investigation.

“[The police] don’t investigate that stuff,” Harris said. “I know three girls who were killed, strangled, and they didn’t do anything.”

Harris had reason to hold this belief. Years later, she reported a man who tried to rape her and stole her phone. CPD put little effort into the investigation, even though tracking her phone would quickly yield the man’s location, Harris said. “Society looks at sex workers like they are nobody,” Harris said. “That’s what makes it so easy for a person to do something to a sex worker.”

Harris acknowledged that officers from some police departments were kinder than others. When she was arrested for prostitution by the Maywood Police, the officers gave her money to get home.

Misconduct varied based on police district—officers in the CPD 8th district were reported to be more degrading toward sex workers, while those in the 7th district are reportedly friendlier, according to the Alliance report. Three of the fifty-one women were murdered in the 8th district, and five in the 7th.

In an emailed statement, a CPD representative stressed that the department does not condone police misconduct of any kind. “Anyone who feels they have been mistreated by a CPD officer is encouraged to call 311 and file a complaint with COPA [the Civilian Office of Police Accountability], which will investigate allegations of misconduct.”

Racism also drives a wedge between law enforcement and sex workers. Years after the stolen phone incident, Harris was among a group of sex workers arrested by Chicago police on the West Side. At the police station, Harris said the white officers offered help to the white sex workers, asking them where their parents were and why they had been in a dangerous neighborhood. The Black sex workers received no such mercy, Harris said.

Women of color are not only mistreated by racist officers; they’re also more vulnerable to sexual violence. Among the fifty unsolved strangulations, seventy-seven percent of the victims were of color, according to data from the Murder Accountability Project.

“Had it been fifty Caucasian women we’d have everybody looking for them, but that’s not the case, is it?” Myers-Powell said.

Prostitution charges financially burden sex workers who are already strapped for cash, and they make it difficult for one to find a job should they leave sex work. A Class A misdemeanor, a common prostitution charge, can result in one year in jail and/or up to $2,500 in fines.

Beyond getting arrested, ceding information to law enforcement can be dangerous. Informants risk violent retribution from murderers and their affiliates, and speaking to the police can wrap one up in court proceedings.

“One thing you don’t do on the street is talk,” Myers-Powell said. “If you do talk, you may have to back up what you said. You might have to testify.”

Instead of talking to the police, Hargrove said survivors are more likely to warn other community members about the killers. “I would be surprised if the community is not aware of some of the individuals warning each other to stay away from this guy or that guy,” he said.

What Hargrove is describing is a phenomenon many sex workers talk about—an informal network of surveillance that exists in lieu of police protection. Harris said she learned about her attacker in the hotel because others had warned her.

In order to solve the murders, law enforcement will have to earn the trust of Chicago’s sex workers. It’s possible, but Myers-Powell isn’t confident it will happen. She said that law enforcement and sex workers live in two different worlds, and that the divide between them is not closing.

Some solutions have proven effective in bridging this gap. The Chicago Prostitution and Trafficking Intervention Court, established in 2015, is a deferred prosecution program that gives arrested sex workers the option to complete a rehabilitation course in lieu of prosecution. Participants receive aid in applying for jobs, obtaining identification cards, securing housing, addressing trauma through Christian Community Health Center and Salvation Army STOP-IT, getting their charges dismissed, and overcoming drug and alcohol addiction. As of September 2019, 396 people had graduated from the program, and many reported a positive experience, according to the Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation.

Hiring former sex workers to work alongside law enforcement has also yielded success. After twenty-five years in the sex trade, Myers-Powell spent ten years with the Cook County Sheriff’s Department’s Human Trafficking Response Team. Along with two other former sex workers, Myers-Powell offered services to arrested prostitutes and trained officers on trauma sensitivity.

“[The girls] would say, ‘We’ve never seen this before but we love it,” Myers-Powell said. “They’d never been arrested and had another survivor there to talk to them and offer services.”

Frazier said former sex workers have a greater capacity to empathize with current sex workers and would therefore be an asset to a homicide investigation.

‘Everybody liked Dellie’

Paul Olson worked for the Cook County Sheriff for thirty-three years. He spent seventeen years in the vice unit, which focuses on so-called public-order crimes like prostitution. During that time got to know numerous sex workers on the West Side. Unlike some of his colleagues, Olson said his time on the job taught him to view sex work as a necessity rather than a choice. He treated sex workers like human beings, which is why he’s still friends with many of them today.

Dellie Jones was one of the women Olson knew well. On August 10, 2002, Olson arrested Jones for solicitation near Cicero Ave. and Division St. When Jones got in his car, she pleaded to be released. “She started crying,” Olson said. “She said ‘Paul, I’m sick of going to jail. I’m dope sick, I lost my kid, and I don’t have anywhere to live.’” Olson issued her a city ticket—a lesser charge than a misdemeanor—and advised her to go to Genesis House, a rehabilitation center for sex workers on the North Side.

“Everybody liked Dellie,” said Frazier, Jones’s sponsor at Genesis House. “She was really sweet. It was just the drugs. She couldn’t stop using.”

One night, Jones left Genesis House and never came back. “I begged Dellie not to leave the day that day,” Frazier said. “She left and got killed that night.”

Jones’ body was discovered on September 7, 2002 in a garage on the West Side. She was thirty-three. Frazier said the police never visited Genesis House to investigate Jones’s murder, which was one of the first among the fifty unsolved strangulation cases.

Olson believes her transient lifestyle likely complicated the investigation. While investigating a homicide, law enforcement tries to determine where the victim was at the time of the murder, who they were with, and why they were with them. In a world where people can disappear for days or weeks at a time, and may be incapacitated by drug use, these crucial details can get muddled.

“A lot of times in a homicide, you get killed by someone you knew,” Olson said. “But these girls are getting into cars with guys they don’t know anything about. They have no idea who they are.” Olson said it can be nearly impossible to figure out when and where a sex worker enters an assailant’s car, and that it’s even harder to determine where they drive to.

To complicate matters more, sex workers may be estranged from family members. “A lot of times when these girls go missing, nobody ever reports them,” Olson said. “Even their family and friends know they’re out on the streets, and it’s not unusual for them to go missing for days or weeks at time.”

Dysfunction within CPD has also hindered numerous homicide investigations. Bill Dorsch, a retired CPD homicide detective turned whistleblower on police misconduct, said he was often rushed from one case to another due to understaffing. “It’s not unusual that you will be working a case very diligently, and suddenly, something else happens and your boss puts you on a new one,” Dorsch said. “You accumulate an awful lot of overtime because you’re going to court, you’re managing your workload; you’re not going home after eight hours.”

Dorsch also said many of his superiors were hired through connections at the department and lacked investigative skills. “The people that get placed in positions of supervision are not the best of the best,” he said. “It’s who you know, that’s how you got there. And that’s tragic.”

Though Dorsch retired from the force in 1994, a 2019 report issued by the Police Executive Research Forum suggests that not much has changed. According to the report, understaffing, lack of equipment, inadequate supervision (of detectives), and disorganization all contribute to CPD’s low murder clearance rate.

Missing postal worker inspires legislation

Kierra Coles, a twenty-six-year-old USPS worker and expectant mother, went missing near her home at 81st St. and Vernon Ave. in Chatham, on October 2, 2018. Her body was never recovered.

Coles’ disappearance deeply unnerved Illinois state Rep. Kambium Buckner of the 26th district. When he began to investigate similar cases, he learned of the fifty unsolved strangulation cases. “Many of these cases have been open for way too long,” Buckner said. “It is unconscionable that with all the resources and technology we have, that we still can’t solve these cases.”

In response, Buckner introduced the Missing and Murdered Chicago Women Act to the Illinois General Assembly in late 2019. The task force would work with CPD to analyze facets of law enforcement that adversely impact violence against women, and to develop alternative solutions to promote community safety. Buckner said he designed this approach to combat victim-blaming. “We know that there is an issue with the way law enforcement deals with these people,” Buckner said. “Specifically the way that these women are often automatically treated like criminals.”

By drawing attention to Chicago’s murdered and missing women, Buckner says the bill would ramp up the investigations into the fifty strangulation cases. “I think [the bill] would have definitely gotten out of committee had we actually had a normal year,” Buckner said. Due to the pandemic, the General Assembly will not reconvene until January 13.

The bill has eight co-sponsors from both parties, including Deputy Majority Leader Jehan Gordon-Booth (D). Buckner said there is no official opposition to the bill, so it will likely pass next year. The bill has yet to be read in committee, where the budget office will release a fiscal note detailing the bill’s cost.

Domestic abuse rises during the pandemic

The bill’s postponement could not have worse timing, though. Data provided by the The Network: Advocating Against Domestic Violence suggests that domestic violence is on the rise. The Illinois Domestic Violence Hotline has seen a 5,597 percent increase in texts and sixteen percent increase in phone calls compared to this time last year, according to data provided by the Network and the city of Chicago’s Department of Family and Support Services.

“Instead of being able to make a hotline call, people have been reaching out via Instagram, Facebook, even Google,” said Megan Rosado of Connections for Abused Women and their Children. Rosado attributed this change to the stay-at-home order—victims at home with abusers are unable to call for fear of retribution. Rosado said survivor services including counseling, crisis intervention, and court advocacy are being offered remotely, which may deter people from seeking help.

“A lot of survivors have to come in person for a session because they don’t have any private space in their home,” Rosado said. Even survivor intervention services offered to hospital patients are now virtual. “It’s more complicated and difficult, especially if somebody is in the hospital, because it requires technology access.”

Rosado said Connections for Abused Women and their Children has had to reduce its shelter capacity by fifty percent. Initially, a grant allowed the program to place survivors in hotel rooms, but the money has since run out. “[The grant] really just got us through the first couple of months of the stay-at-home order,” Rosado said. Now, the program is operating at reduced capacity.

Some organizations, however, continue to offer in-person services. Myers-Powell said the pandemic has made it difficult to find twenty-four-hour rehabilitation centers and safe housing for survivors of sex trafficking. “We are still doing the same work that we’ve always done because we are a crisis program,” Myers-Powell said. “But imagine trying to do crisis work when the whole country is under crisis.”

And with the increasing unemployment rate in Chicago, which skyrocketed to 17.5 percent in April according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics, more people may be turning to the street economy. Mahoganey Harris fears younger and more inexperienced women are entering the profession.

“Because of COVID, the newer, younger generation of people—women suffering from drug addiction or domestic violence—are on the streets,” Harris said. “And there’s no help available right now.”

Vickie Smith, executive director of the Illinois Coalition Against Domestic Violence, acknowledged the dangers in delaying the house bill, but she also said that rushing into legislation can have unintended consequences. “There has been a lot of good that has come out of this,” Smith said of the shutdown. “It’s much better to take the time to develop [a bill] that’s really well thought out.”

Poor legislation can fuel the prison-industrial complex, which disproportionately affects Black and brown people and doesn’t ameliorate domestic violence, Smith said. She also views the shutdown as an opportunity to redesign outdated services for survivors of abuse and hopes to use this time to design services that will better serve the needs of immigrants, people of color, and members of the LGBT+ community.

Her first suggestion? To listen.

Kira Leadholm is a Chicago-based freelance journalist who writes about social justice and music. She is currently earning an MSJ from Medill School of Journalism and has a B.A. from the University of Chicago. This is her first piece for the Weekly.