The 2019 budget President Donald Trump unveiled Monday is not a substitute for the two-year spending plan Congress approved last week. But it could serve as a blueprint for how Congress allocates funds in the years to come. And in that plan, the Trump administration wants an almost complete reworking of Medicare and Medicaid, reducing spending by $554 billion over the next decade. The White House says the savings come from reforms, not cuts. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, for one, disagrees.

“If you were wondering how President Trump plans to pay for his massive tax cuts to millionaires, billionaires and large corporations, this budget answers that question for you: by breaking his campaign pledge not to cut Medicare, Medicaid, and social security,” Sanders said during a hearing with White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney. “In fact, President Trump’s budget would slash Medicaid by over $1.3 trillion, cut Medicare by over $500 billion, and reduce social security by nearly $25 billion.”

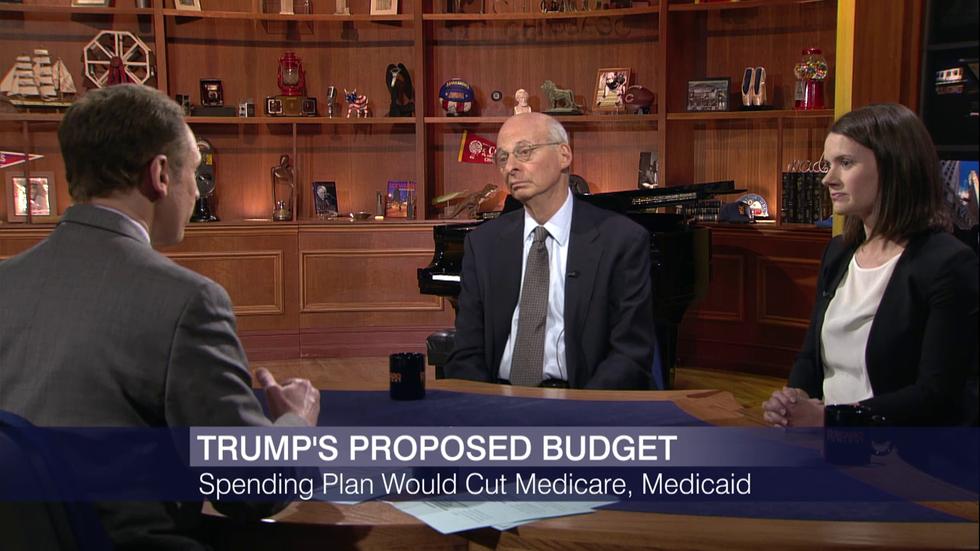

How would those cuts affect people enrolled in the programs – and are they good health policy? Richard Baehr, a health care consultant and chief political correspondent for the online publication American Thinker, says proposed changes to Medicare aren’t particularly drastic, but the changes to Medicaid are significant and needed.

“I personally think putting Medicaid on a budget is not an unreasonable approach and giving some flexibility to the states is also a pretty good idea,” Baehr said. “There might be some states that would be sort of harsher in this than others. But in general, looking at Medicaid as a laboratory, you can’t do any worse than the program has been up to now.”

Amanda Starc, associate professor at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management who studies health insurance and economics, agrees that the Medicaid cuts are the more significant. But she disagrees that they’ll be good for the program.

“States will probably end up making some cuts, either to who’s covered or what services are covered. To the average Medicaid beneficiary, to the extent any of this becomes law, this is not a good thing,” Starc said. “If you look at the set of people on Medicaid we could actually expect to work a full-time job, it’s actually quite small.”

And, she thinks it will cost states more to enforce the work requirements than it’ll save them. “The juice is not worth the squeeze.”

One thing Starc and Baehr agree on: after a series of failed health reform bills during 2017, the Republican-controlled Congress is unlikely to take up potentially unpopular proposals during an election year.

Baehr and Starc join Chicago Tonight for a conversation.